Breaking All Bounds: American Women Artists (1825-1945), An Exhibition and Sale

- NEW YORK, New York

- /

- November 08, 2018

Hawthorne Fine Art in New York now presents a new group show entitled, “Breaking All Bounds: American Women Artists (1825-1945), An Exhibition and Sale.” The majority of the works from this show date from the period in the nineteenth century when academic training was primarily for men. Beginning in the Gilded Age, during the rise of artists like Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) and Cecilia Beaux (1855-1942), women artists became increasingly active participants in the American art scene. As art historian Laura Prieto writes in her book on professional women artists, women eventually gained access to commissions and education because “American art schools simply could not afford to bar women students from attending classes.”i Thus by 1844, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts was accepting female students, signaling the “beginning of women artists’ access to indispensable professional credentials.”ii

This fall, “Breaking All Bounds” will bring together artworks that demonstrate the range of academic subjects mastered by many of these female artists. Included are several that depict domestic, intellectual pursuits such as reading and crafting. In A Quiet Moment (1896) by Maria R. Dixon (1849-1897), a graceful woman is shown engrossed in her favorite book. Dressed in a white cotton dress and framed by Japonisme-style wallpaper, Dixon’s heroine embodies Victorian ideals of beauty. In a similar painting by Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones (1885-1968) of needlepoint stitching called Woman in an Interior, the lady of the house is again shown at home. Together, these two works illustrate the expectations for refined women at the time, who were expected to “build and maintain beautiful, cultivated homes” through studying and practicing art.iii In another work by Claude Raguet Hirst (1855-1942), the artist depicts the things they needed for these creative pursuits: a burning candle, reading spectacles, and beloved books.

Portraits of prominent local women at the turn of the nineteenth century also conjure the joie de vivre of emerging female artists. In an exquisite example of early colonial painting, Anna Claypoole Peale (1791-1878) painted the portraits of the Reverend Obadiah Brown of the First Baptist Church and his wife Elizabeth Brown on ivory in 1819. A member of the Philadelphiaarea Peale family and niece of Charles Wilson Peale, Anna was encouraged to be an artist by her family at a time when most women were discouraged from becoming professionals. Peale became renowned for her skill at capturing the life of her sitters in exquisite detail and later received commissions to paint presidents James Monroe and Andrew Jackson.

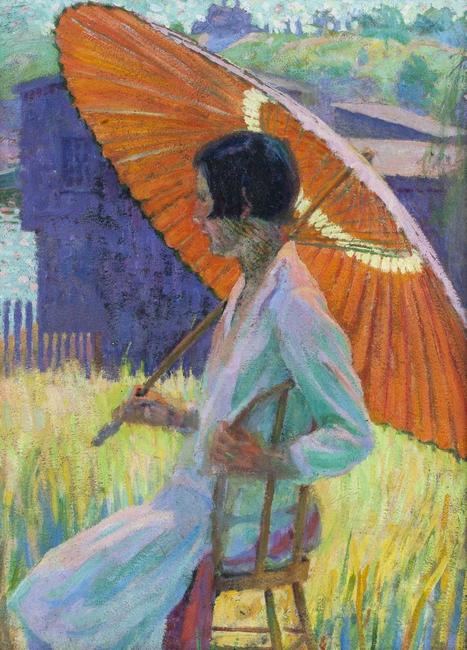

Almost a hundred years later, the illustrator and painter Grace Cochrane Sanger (b. 1881) continued this tradition by portraying the lifestyles of creative women. After beginning her career illustrating for the Ladies’ Home Journal in 1910 and later for the novel Eve Dorre: The Story of Her Precarious Youth by Emil Vielé Strother in 1915, Sanger expanded her skills into oil portraits on canvas. In her painting Woman with Red Parasol, Sanger captured a young woman wearing the popular flapper-style bob haircut posing with a paper parasol in a garden. This celebratory work completed in the Art Deco style exemplifies the spirit of the Roaring Twenties. Similarly, Margarett W. McKean Sargent (1892-1978), a cousin of the Gilded Age painter John Singer Sargent (1856-1925), also depicted the independent ‘New Woman’ of the 1910s and 1920s.iv Sargent’s sculpture Stepping Out from 1916, skillfully cast in bronze, shows a woman stepping forth – embracing the momentum for women artists of the period.

Another artist who painted observations of daily life was Felicie Waldo Howell (1897-1968). A graduate of the Corcoran Art School, Howell painted scenes that others might typically overlook in works like Red Cross Parade, NYC from 1917. In this painting of a crowd of mostly women and children, Howell uses the impressionist style to portray the excitement of city life. As the light dapples the nearby trees, the stars of the parade, including a large elephant, stride past the red cross volunteers through a public New York City park. Following in the footsteps of American Impressionist painters like Maurice Brazil Prendergast (1858-1924) and Childe Hassam (1859-1935), Howell leaves the work unfinished to capture the liveliness of the scene.

Landscape painting also became a significant subject for women who wished to be seen as serious artists during the first two decades of the twentieth century. In a tranquil landscape from 1918, Caroline Lord (1860-1927) painted a serene journey along a still river. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio to the president of the Indianapolis and Cincinnati railroads, Lord’s work displayed traditional vignettes and built on the compositions of the Hudson River School. This specific work, Along the River Bank from 1918, of a river bend is reminiscent of the well-known painting Arques-la-Bataille from 1885 by another artist born in Cincinnati, John Twachtman (1853-1902). Now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Arques-la-Bataille shows a river cast over by a sizable shadow– one of the major features of Lord’s painting Along the River Bank.

The landscapes of Agnes Richmond (1870-1964) were influenced by the impressionism of the American Ashcan style. Richmond, who studied and taught at the Art Students League, most notably under John Twachtman (1853-1902), painted bright, expansive American scenes. In Gloucester Rocks, Ten Pound Island (c. 1914-15), Richmond’s sketchy, loose brushstrokes capture a local view of an inlet in the harbor of Gloucester, Massachusetts. The painter Hortense Tanenbaum Ferne (1889-1976) exhibited a similar skill in her painting Activity from circa 1935 of a bustling New York City harbor. A view of the Financial District from Brooklyn Bridge Park, Activity portrays the thriving economy of the East River, the brand-new Woolworth Building, and the influence of her teacher and mentor William Merritt Chase (1849-1916).

Professional women artists also displayed an interest in two other areas of academic art education: nature studies and still life. The first female member of the American Watercolor Society, Fidelia Bridges (1834-1923) often painted decorative studies of intricate flora and fauna as seen in the watercolor Birds in a Marshland Landscape from 1874. Original paintings like these became so popular that they were reproduced in the 1880s and 1890s as chromolithographs by the printer Louis Prang.v Bridges, whose art-deco artworks were also printed as greeting cards and calendars, became one of Prang’s most popular designers. Such was the prominence of print culture in the nineteenth century that Prang held exhibitions of original works by his designers in 1875, 1892, and 1899, which he also advertised and published in elaborate catalogues.vi

Nature studies were a celebrated art form for women of the late nineteenth century. The artist Sophie Ley (1849-1918) also mastered the art of the floral painting in 1893 with Still Life with Cherry Blossoms. Born in Germany, Ley’s art nouveau-style reflects the popularity at the time of stylized depictions of the picturesque. A vision of floral abundance, Ley’s still life was also exhibited at the Women’s Pavilion at the Chicago World’s Fair and Columbian Exposition in 1893. As art historian Wanda Corn writes, these separate buildings at American international fairs promoted the value of woman’s work outside the home and were centers for debates on education, dress reform, and even suffrage.vii While “Breaking All Bounds” focuses on later nineteenth and early twentieth century masterpieces, it also includes works by female predecessors who painted in the Hudson River School and Luminist modes. One such talent was Susie M. Barstow (1836-1923), an astute observer of the local environment of New York state who reportedly climbed more than 110 mountain peaks in her lifetime.viii As seen in chilly winter scenes like November Frost in the Mountains, Barstow skillfully recreated her intrepid experiences. Born in Brooklyn to a tea merchant, Barstow was one of few female artists of the mid-nineteenth century who rose to prominence without family connections to the art world. Through her art, as one writer states, Barstow “challenged all notions of good behavior by climbing local mountains and painting as she went” because she dared to “imagine a larger world for herself.”ix

At the height of academic painting in the late nineteenth century, women artists were gaining notoriety while also becoming recognized as professionals. The painter Mary Jane Peale (18271902), granddaughter of Charles Wilson Peale and distant cousin to Anna Claypoole, received an education appropriate for a descendent of American artistic royalty. After apprenticing with her uncle Rembrandt Peale (1778-1860) and later with the portrait painter Thomas Sully (17831872), Mary Jane attended the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. In Still-Life with Fruit and Flowers, Mary Jane composed a classical still-life in the tradition of the Northern Renaissance masters such as Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), the namesake of her father Rubens Peale.

Many of the works in “Breaking All Bounds” contribute to our understanding of how increased access to academic art education shaped the careers of late nineteenth and early twentieth century women artists. The artworks in this exhibition illustrate the range of subjects, styles, and educational backgrounds of women artists of the late Gilded Age and early Impressionist period. As the art historian Griselda Pollock has written, these artists were attracted to Impressionism because it legitimized “subjects dealing with domestic social life hitherto relegated as mere genre painting.”x Women artists emerging during this period were adept with all of the subjects open to their male peers: the home, the neighborhood, the city, nature, and the wilderness.

“Breaking All Bounds: American Women Artists (1825-1945), An Exhibition and Sale” is available for view by appointment at 12 East 86th Street, NYC, from November 1st, 2018 through January 11th, 2019. For more information or to make an appointment during gallery hours, please contact info@hawthornefineart.com or (212) 731-0550 by phone. While a select few paintings are highlighted here, the entirety of Hawthorne Fine Art’s diverse collection is accessible through the Inventory page of the gallery website, HawthorneFineArt.com. The over fifty artworks displayed in this exhibition will be available for sale, with a catalogue available through the gallery website at HawthorneFineArt.com/catalogues.

i Prieto, Laura R. At Home in the Studio: The Professionalization of Women Artists in America (Cambridge: Harvard University, 2001), 25.

ii Ibid.

iii Prieto, 22.

iv For more information on the ‘New Woman’ archetype that emerged in the 1880s and influenced American female identity through the interwar years, see the following sources: Connor, Holly Page. Off the Pedestal: New Woman in the Art of Homer, Chase, and Sargent (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2006) and Patterson, Martha H. ed., The American New Woman Revisited: A Reader, 1894-1930 (New Brunswick: Rutgers University, 2008).

v Foster, Kathleen A. American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent (New Haven: Yale University, 2017), 159.

vi Foster, American Watercolor in the Age of Homer and Sargent, citation 30, 424.

vii Corn, Wanda, et al. Women Building History: Public Art at the 1893 Columbian Exposition (Berkeley, CA: University of California, 2011), 65.

viii Barstow was an active member of the Appalachian Mountain Club.

ix Von Glahn, Denise. Music and the Skillful Listener: American Women Compose the Natural World (Indianapolis: Indiana University, 2013), 15.

x Pollock, Griselda. “Modernity and the Spectacle of Femininity,” in Norma Broude and Mary d. Garrard, eds., The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History (New York City: Harper Collins, 1992), 248.

100x100_c.jpg)