Pulitzer Illuminates New Aspects of Medieval Art Through the Lens of Ecology

- ST. LOUIS, Missouri

- /

- January 17, 2023

This spring the Pulitzer Arts Foundation presents The Nature of Things: Medieval Art and Ecology, 1100-1550, a ground-breaking exhibition that explores how artmaking impacted the environment and, inversely, how the natural world shaped artistic practices in Europe during the second half of the Middle Ages.

With approximately 50 sacred and secular objects on loan from 18 institutions, The Nature of Things invites the viewer to think in new ways about archetypal forms of medieval art, from a radiant stained glass window panel to a wall tapestry teeming with flora and fauna to a carved wooden fragment of the bowed head of the crucified Christ. The exhibition also poses questions about the environmental impacts of contemporary exhibition-making and the nature of museum practice.

On view from March 10 through August 6, 2023, The Nature of Things: Medieval Art and Ecology, 1100-1550, has been organized by Heather Alexis Smith, Assistant Curator, Pulitzer Arts Foundation.

“We hope that The Nature of Things performs a valuable service on a number of levels. The presentation sheds new light on medieval art; unearths links between the ecological concerns of a long-ago era and those of the present day; and offers a model for contemporary exhibition organization. The team here has worked to reduce the carbon footprint of the project,” says Pulitzer Executive Director Cara Starke.

“Living as we do today in a world where paint comes in a tube and wood from a lumber store, it’s easy to dissociate the work of art from its material links to the natural world. The Nature of Things is intended to illustrate how artists in Europe once directly depended on a raft of industries—forestry, quarrying, mining and farming—to source the raw ingredients for their works, industries that left both temporary and permanent marks on the landscape,” says Heather Alexis Smith.

EXHIBITION OVERVIEW

The Nature of Things immerses the viewer in the quotidian concerns of the era, a time when cycles of scarcity, abundance, and ecological change determined the materiality of Europe’s most sumptuous luxury goods. The exhibition is divided into four sections by the type of medium and its source: Forest (wood); Field (materials derived from plants and animals); Earth (glass and ceramics); and Quarry and Mine (metals and stone). Each section is accompanied by a digital kiosk illustrating how the materials were grown, gathered, and transformed into artworks.

Forest

Wood was at the center of survival and industry in the Middle Ages. The section explores wood as a key constituent of medieval architecture, painting, and sculpture and demonstrates how trees and forests were charged with layered meanings: on the one hand, woodland spaces were used for hunting and pleasurable gatherings, and on the other, they were settings that evoked superstitions, fear, and apprehension, or even the divine. The section also explores the environmental costs that came with harvesting wood.

Three free-standing carved wood figures intended for ecclesiastical use dominate the first gallery. Two are oak and one limewood, a wood preferred for carving because of its pliancy and fine grain. Those qualities are apparent in the razor-thin curls on the sinuous beard of St. Anthony, a limewood figure carved around 1500 CE. Less evident today are the spiritual and healing properties that medieval people attributed to limewood, which may have further imbued the work with meaning.

Created at the same time and on view nearby is a carving of the bowed head of the crucified Christ carved from oak. In its day, the sculpture would have been brightly polychromed. The wearing away of the original paint finish reveals how the wood’s hard grain and natural growth patterns guided the artist in shaping the form and brought particular character to the carving.

The visitor may be surprised to encounter an oil painting in the “Forest” section. But in the Middle Ages artists often painted on wood boards, which were well suited for portable objects of private devotion. “The Vision of St. Eustace” (ca. 1500) depicts the patron saint of hunters in a wooded area at the very moment he encounters a stag with a crucifix glowing between its antlers.

A beautifully illustrated Book of Hours made in the early 16th century in France is also in this section, opened to a page devoted to St. Francis, known today as the “patron saint of ecology.” St. Francis instructed his followers to protect the natural world and respect living creatures as manifestations of God’s will. The manuscript page is one of the book’s 33 miniatures painted on vellum, a smooth and durable material made by skinning and processing the skin of a sheep, goat, or cow. The ink was made from a mixture of oak gall, a substance extracted from oak trees.

Also in this gallery is a small wooden object that in another museum exhibition could easily be overlooked. An architectural element known as a “boss”—a block of wood that fits over ceiling ribs like a keystone—is displayed here among other architectural fragments that illustrate the hallmarks of the Gothic style: naturalistic carvings teeming with flowers, foliage, and animals, both real and imagined. The boss invites the viewer to wonder if the wood carver enjoyed the fact that his decorative scheme—an arabesque of oak leaves and acorns—echoed its own surface, a block of oak.

Field

This section features objects made of materials derived from plants and animals. Commanding the gallery space is a large and magnificent millefleurs (“thousand-flower”) tapestry created between 1500 and 1525 in what today is Belgium. Against a pictorial background studded with jewel-like blossoms, stems, and grasses is an array of frolicking animals. Some must have been familiar to the master weaver—a goat and rooster limp in the mouths of wild carnivores; a prancing stag; a braying dog; a reclining ram; and a colony of rabbits. Others were drawn from lore, including in the lower right corner a unicorn (often an allegorical symbol of Christ). This example of medieval imaginative powers wrought in wool is on view outside its home institution, the Cincinnati Art Museum, for the first time in over 40 years.

Such a wall tapestry was a symbol of wealth and status that required extraordinary skill and months of dedicated labor to produce. Such wall hangings also functioned as an early form of insulation and a kind of mini-environment. Smith notes that “during dark, cold days of winter confinement, vivid scenes like these spurred the imagination and served as a welcome daily reminder of the promise of spring.” Indeed, some art historians have noted that tapestries became popular around the time that the “Little Ice Age” struck. This period of climate change lasted from about 1300 through 1850, causing wet weather and frigid temperatures.

The high demand for wool—as well as parchment for manuscripts—also had environmental consequences during the Middle Ages. Huge swatches of land were developed for animal herding, sometimes pitting shepherd, farmer, and woodcutter against one other. A loss of biological diversity resulted from sheep grazing in particular, as these animals have a tendency to overgraze, leading to a reduction in vegetation and subsequent soil erosion.

Nearby the large woven expanse of flora and fauna is an herbal open to a page with two woodblock illustrations of herbal plants. An example of an incunable, or an early printed book, the 15th-century herbal was produced in Germany for therapeutic use. Its pair of green leafy herbs are accurately illustrated by careful observation, some 200 years before the taxonomy of Linnaeus.

By the 13th century, the process of making paper out of hemp and flax was established in Europe, brought to Spain through contact with Asia and the greater Islamic world. This development added to the demands that artmaking was already making on the landscape of Europe. Early medieval book production is represented in The Nature of Things by a folio from the "Pink Qur’an,” a 13th-century Qur’an named after the color of its paper, which was likely fabricated in Southern Spain at the earliest known paper mill in Europe. The verses on the page describe the contrasting eternities for sinners (the flames of hell) and the faithful (a paradisiacal garden), a subject conveyed in five lines of text in bold script with diacritical and vocalization marks in gold and blue.

The growing demand for silk also contributed to the mosaic of environmental change in Europe. Featured in The Nature of Things is an amber colored brocaded silk curtain, on loan from the St. Louis Art Museum, which was woven in the late 14th century in a pattern of eight-pointed stars on a complicated arabesque ground. The growing demand for silk luxury objects meant stepping up trade with Asia, as well as introducing non-native species of silkworm into the European ecosystem. Because silkworms subsist on mulberry leaves, silk makers in Spain planted vast acreages of mulberry trees, until there were as many as 3,000 silk making farms in Southern Spain.

Ivory was another privileged material in the Middle Ages. To satisfy the huge demand, countless elephants were slaughtered for their tusks and a transcontinental trade was developed between Europeans, who exported commodities like wool and copper, and traders in North and West Africa, who exported ivory, the textile dye fixative alum, and other valuable materials. “Cover for a Writing Table with a Romance Subject,” attributed to the French Atelier of the Boxes (1340-1360), is one of two fine objects carved of ivory featured in the exhibition.

When ivory was unavailable or the price prohibitively high, artisans turned to a substitute—bone. Two masterfully carved bone boxes are seen here, one ornamented with small buttery hued panels of scenes from the life of Christ fashioned by the 14th-century Venetian atelier of Baldassare degli Embriachi. The workmanship outstrips the common, even ignoble, materials of bone, stained horn, and wood from which the small casket was made. The Embriachi found a market for such fine bone boxes in the rising merchant class of the late 1400s and early 1500s while incidentally reducing waste through their use of scrap bone.

Earth

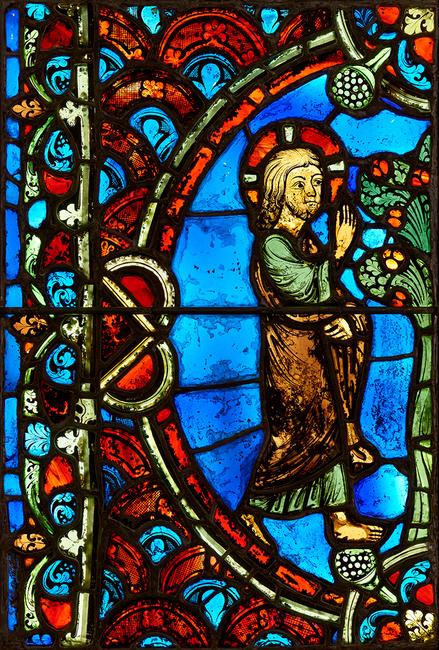

The art form most associated with the Middle Ages greets the viewer in the final gallery, a glowing blue, red, green, and gold stained-glass window that originally would have resided in the 13th-century cathedral in Troyes, France, its narrative showing God and the Tree of Knowledge as he warned Adam and Eve not to eat its fruit in the Garden of Eden.

The main medieval process for making glass required sand and wood ash (potash). By 1250 CE, when this panel was made, the demand for glass also had extended into domestic life, as can be seen in three nearby glass beakers made between the 13th and 15th centuries. “Forest Glass Beaker” (1500 CE) has a triangular form jutting up from its base. This “kick” strengthened the glass’s structure so that it was less likely to shatter while cooling in the annealing oven.

Scholars believe that medieval glassmakers developed the kick to minimize breakage, reducing waste and in turn, decreasing the amount of firewood they used (not to mention saving on costs). Wood was, after all, essential for a raft of other industries, and the increased consumption required by glassmaking added to the problem of deforestation and shortages, which plagued medieval communities.

Medieval potters also developed ways of reducing the amount of wood needed to produce their crafts. One result was salt-glazed stoneware, made by adding salt to the kiln as the ceramics were firing. The chemical reaction produced a thin-pebbled glaze, meaning that the wares only had to be fired one time. Unfortunately, the salt-glazing process also released clouds of toxic fumes, causing health hazards and environmental pollution. In the mid 16th century, some German cities banished potters because of concerns over pollution and wood consumption. The exhibition includes a pebble-surfaced earthenware jug from the town of Frechen, Germany, where many of the exiled potters settled. Under the jovial face of a common motif of the era, a bearded “wild man” is a girth-girdling band inscribed three times in relief, “Hooray for a good drink!”

Also on view in this section is a large, tin-glazed earthenware dish from Spain that is vividly ornamented with a sketch of a blue bird. Such tin-glazed wares were sought after as prestige objects, in part due to the costly materials required for their manufacture. The creamy surface of this object was the result of tin glazing, a process that required obtaining tin that was likely mined in southwestern England. The vibrant blue glaze used in the design came from cobalt, likely mined in Germany, Morocco, or as far away as Iran. Wares like this testify to the sophisticated long-distance networks that supplied medieval artists with materials. They also reveal how the demand for artmaking ingredients in one place might exert environmental pressures hundreds or even thousands of miles away.

Quarry and Mine (Stone Metal)

The four centuries between 1100 CE and 1500 CE saw a spike in the building of massive stone architecture in Europe. It is estimated that millions of cubic feet of stone were required to build the 500 large cathedrals and thousands of small churches and monastic compounds that were constructed during this era. Unlike wood and many other artisanal materials made from plant and animal matter, stone is non-renewable. The Nature of Things examines how quarriers permanently transformed the land, leaving huge pits in the earth or flattening hillsides as they removed giant blocks of stone.

The architectural fragments on view in this section testify not only to how construction can disrupt landscape but also to how geologic forces might guide the selection and use of a particular stone. Limestone and marble were frequently sought after for the carving of architectural ornamentation because of their relative softness, and examples of both are represented in the show.

Among seven carved stone architectural fragments on view in this section is an exceptional marble column depicting the apostles Matthew, Jude, and Simon looking out at the viewer, with their backs to one another. It is one of four such columns depicting the 12 apostles that once supported the altar in a Benedictine abbey next to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. The configuration literally embeds the Medieval conception of the apostles as pillars of the church into the very structure of the altar.

Another material especially favored by sculptors after the mid 14th century was alabaster, an incredibly soft stone, lying only a foot or two underground. Requiring minimal labor to quarry and carve, alabaster was well-suited to a European continent whose population had been decimated by the Black Death.

As the visitor steps into this gallery, they will also encounter a variety of precious liturgical objects fashioned from gold, silver, bronze, and copper. Their brilliance and durability served the need of the Christian faithful for artifacts that were visual equivalents of God’s amplitude, purity, and perfection.

An illuminated manuscript made in Paris around 1400 CE is featured here, opened to a page illuminated with gold leaf, its miniature scene framed by floral borders, illuminated capitals, and line ornaments. Also in this gallery are a bell-shaped bronze censer trailed by a long chain and hanging loop; a copper-gilt, enameled relic case from Limoges; and a copper- and silver-gilt glass monstrance from Germany that is all delicate Gothic tracery.

“The dazzle of gold had a spiritual significance during the Middle Ages, when light was considered a manifestation of the divine,” notes Smith. The gold that Europeans so ardently desired was mainly acquired from West Africa in exchange for a variety of European commodities including copper and wool.

Premodern miners tunneled through the earth and stripped topsoil to reach precious ores, sometimes razing whole landscapes, particularly in southern and eastern Germany, where copper and silver mining were major industries. A highlight of this section of the exhibition is a copper alloy aquamanile in the shape of a lion from Lower Saxony. The ewer would likely have been used for the ceremonial washing of hands as part of the Christian Eucharist or in secular settings at mealtimes. Medieval art was not without wit: the water spouted from the lion’s mouth.

Making the Exhibition

Like many museums around the world, the Pulitzer Arts Foundation is grappling with questions of sustainability and ecological impact. For The Nature of Things, the Pulitzer cut fuel consumption by only borrowing artworks domestically, rather than shipping artworks internationally, even though the largest collections of Medieval Art are in Europe. Key international objects are represented instead through digital kiosks throughout the exhibition. Furthermore, pedestals and vitrines from prior shows are reused and the production of new exhibition materials are limited. These efforts are part of the Pulitzer’s larger endeavor to understand its ecological impact.

About the Pulitzer Arts Foundation

Located in the heart of St. Louis, the Pulitzer Arts Foundation presents art from around the world in its celebrated building by Tadao Ando and in its surrounding neighborhood. Exhibitions include both contemporary and historic art and are complemented by a wide range of free public programs, including music, literary arts, dance, wellness, and cultural discussions. Founded in 2001, the Pulitzer is a place where ideas are freely explored, new art is exhibited, and historic work reimagined.

In addition to the museum, the Pulitzer has several outdoor spaces: Park-Like–a native plant rain garden; the Spring Church–a roofless pavilion and beloved landmark; and the Tree Grove–a quiet, shady picnic spot. The museum is open Thursday through Sunday, 10am–5pm, with evening hours until 8pm on Friday. The outdoor campus is open daily, sunrise to sunset. Admission is free. For more information, visit pulitzerarts.org or on social media @pulitzerarts.

270x400_c.jpg)

![Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640), After Titian (Tiziano Vecelli) (Italian [Venetian], c. 1488–1576), Rape of Europa, 1628–29. Oil on canvas, 71 7/8 x 79 3/8 in. Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640), After Titian (Tiziano Vecelli) (Italian [Venetian], c. 1488–1576), Rape of Europa, 1628–29. Oil on canvas, 71 7/8 x 79 3/8 in.](/images/c/e2/2e/Jan20_Rape_of_Europa100x100_c.jpg)