Looking North and South Considers Early European Prints at the Clark

- WILLIAMSTOWN, Massachusetts

- /

- February 26, 2017

Looking North and South: European Prints and Drawings, 1500–1650, on view at the Clark Art Institute March 5–May 29, 2017, explores the character of artistic exchange among artists working in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as seen in prints, drawings, and rare books from the Clark’s permanent collection. Northern artists, predominantly those in the Netherlands and Germany, traveled increasingly to southern Europe—particularly Italy—during this time, responding to Italian art and antique statuary. The circulation of artistic ideas, practices, and traditions resulted in a dialogue of inspiration and innovation across the continent.

Looking North and South examines how artists responded to the work of their contemporaries in different regions of early modern Europe, revealing varying modes of artistic production and the important role of works on paper in shaping the exchange of ideas. Thirty-four works from the Clark’s permanent collection and from the Clark’s Julius S. Held Rare Book Collection are presented in the exhibition, including works by Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471–1528); Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606–69); Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640); Guercino (Italian, 1591–1666); and Giorgio Vasari (Italian, 1511–1574).

“The Clark’s collection of Old Master prints and drawings is extraordinary in its breadth, depth, and quality,” said Olivier Meslay, Felda and Dena Hardymon Director of the Clark. “It is remarkable to be able to present an exhibition of this size and quality with works entirely from our permanent collection.”

Looking North and South considers approaches to drawing practices and education, depictions of the body and narrative subjects, and the dynamics of printmaking and artistic collaboration. Prints moved easily across large geographical distances, passing between artists and collectors and making ideas and artistic forms available to wide audiences. Drawings—from the highly finished to the loosely executed—offer insight into artists’ working processes and creativity.

“In highlighting the complexity of artistic exchange across Europe in this period, the exhibition encourages viewers to think broadly about artists and their work in more connected ways,” said exhibition curator Lara Yeager-Crasselt. “By raising questions about process and material, the exhibition encourages close looking in a particular way. Seeing some of these works side-by-side allows the viewer to think about what northern and southern artists were interested in depicting, how they were making these works, and how they were responding to each other—or in some cases not responding at all.”

Drawing the body is a fundamental aspect of artistic learning and has served as one the first steps in an artist’s education since the Renaissance. Artists in the Netherlands and Italy approached the depiction of the body in different ways because of their respective traditions or training, yet their artistic challenges in representing the body—whether from life or from antique sculpture—and handling light and shadow were similar. In Andrea del Sarto’s (Italian, 1486–1530) chalk drawing Study of Drapery (1510–13), the artist created an exquisite preparatory work, likely rendered from a studio model, that addresses the interplay of light and shadow as it falls over the folds of cloth. In contrast, Head of a Woman (c. 1495–1497) by Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (Italian, c. 1467–1516) is a precise and delicate example of a finished, possibly independent drawing that follows the tradition of Leonardo da Vinci in using sfumato (gradual shading) in the depiction of the human form.

Albrecht Dürer’s representations of the human body were admired throughout Northern Europe. In his engraving Adam and Eve (1504), Dürer applied a system of proportions to achieve what he considered an idealized human form. Based on his study of the ancient Roman theorist Vitruvius, as well as antique statuary he encountered in Italy, Dürer developed a set of ideal measurements that would later appear in Four Books on Human Proportion (1528).

Conversely, Jacopo Palma il Giovane’s (Italian, c. 1548–1648) Ten Head Studies (1636) utilizes the drawing method of deconstructing the human form, which he helped popularize in Venice. The figures, seen from various perspectives and representative of different ages and types, are interspersed with depictions of eyes, noses, and ears. Although the origins of this print are unknown, it relates to images found in drawing books, which formalized a method of progressive learning around the human form. This approach quickly spread to Northern Europe, where drawing books were used by art students and amateurs alike.

Similarly, Abraham Bloemaert (Dutch, 1566–1651) intended the Tekenboek (c. 1650)—one of the few Dutch drawing books produced in the seventeenth century—to serve as a teaching tool for young art students and amateur artists. The drawing manual, published by the artist’s son Frederick Bloemaert (Dutch, 1616–1690) shortly after his father’s death, included prints of figures, anatomical studies, animals, and various narrative compositions. Images of bodily fragments such as heads and hands served as models for students to copy. Through these teaching manuals, students could learn how to study the body in isolated segments, independent of a teacher.

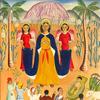

Looking North and South also examines the varied approaches to and functions of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century narrative drawings and prints by northern and southern European artists. Highly detailed Italian drawings such as Vasari’s The Incredulity of Saint Thomas (c. 1556–57) are preparatory works conceived for paintings. Several seventeenth-century Dutch drawings, like Rembrandt’s Nathan Admonishing David (c. 1652–53), show the power of storytelling through a seemingly rapid manner of execution.

The exhibition also considers the role of printmaking in the widespread dissemination of these images across Europe. Prints contributed significantly to the spread of artistic ideas as well as to linking artists, printmakers, publishers, and collectors in new ways. Issues related to artists’ ownership of the images, both adversarial and collaborative, are explored through considering works by Dürer and Rubens and replicas of their originals made by printmakers Marcantonio Raimondi (Italian, 1470–before1534), Boetius Adams Bolswert (Flemish, 1590–1633), and Schelte Bolswert (Flemish, 1581–1659).