Disclosure: Confessions for Modern Times at Durden and Ray

- LOS ANGELES, California

- /

- January 09, 2019

Curators: Dani Dodge and Alanna Marcelletti

Artists: Kim Abeles, Jorin Bossen, Kimberly Brooks, Joe Davidson, Dani Dodge, Donald Fodness, Kathryn Hart, Debby and Larry Kline, Conchi Sanford, Ed “Celso” Tahaney and Steven Wolkoff

January is about cleansing the past and making new starts. But since the early 1990s, independent polls have shown the rapid growth of those without a religious affiliation. So where do people go to confess, if not to a higher power? Two curators thought … perhaps an art gallery?

Through Feb. 2, 2019, Durden and Ray in downtown Los Angeles will celebrate the start of the year with an exhibition that allows people to cleanse their souls through the art of disclosure.

Curated by Dani Dodge and Alanna Marcelletti, “Disclosure: Confessions for Modern Times” features artists Kim Abeles, Jorin Bossen, Kimberly Brooks, Joe Davidson, Dani Dodge, Donald Fodness, Kathryn Hart, Debby and Larry Kline, Conchi Sanford, Ed Tahaney and Steven Wolkoff.

The exhibition opened with a reception from 7 to 10 p.m. Saturday, Jan. 5, 2019, and closes Feb. 2, 2019. The gallery is open Saturdays and Sundays, noon to 5 p.m. Durden and Ray is located in the Bendix Building in LA’s Fashion District at 1206 Maple Ave., #832 Los Angeles, CA 90015. www.durdenandray.com

For this exhibition, Dodge and Marcelletti decided to play devil’s advocates and create a space where the participants can disclose transgressions and progress unfettered into 2019 through art. The exhibition includes interactive confessionals, each designed by different artists, and figurative art exploring the experience of being human through relationships, tragedy, translation of autobiography and Barry Manilow.

The show is a contemporary take on the sacred and secular acts of confessing sins. Conchi Sanford’s confessional is composed of two see-through cocoons that allow people to whisper secrets to each other. Steven Wolkoff channels Bart Simpson with a piece on which people write what they will not do. Inside Kim Abeles’ confessional, people hear the sound of audio she collected one minute every day for 1440 minutes, or 24 hours, and Dani Dodge’s formal wooden confessional flashes “CONFESS” while inviting people to put their sins on display through Post-it notes.

“It’s not as if we aren’t aware of our own failings,” said Alanna Marcelletti, who identifies as a vague Catholic. “With our pervasive attention to social media, we witness the rampant documentation of repulsive things that people do to each other. And we are acutely aware of how much those terrible acts relate to who we are in secret.”

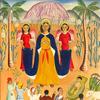

The figurative works in the show acknowledge the burden of unreleased guilt. Aesthetically, they are divided by the curators into their ideas of heaven, hell and in-between. Kimberly Brooks’ abstract figures exist in a heavenly realm, while Donald Fodness hellishly disassembles Barry Manilow. Debby and Larry Kline play prophet by mapping impending tragedy for the planet referencing Biblical plagues as they foretell natural and manmade disasters. In between are the paintings of a disconnected relationship by Jorin Bossen, and Ed “Celso” Tahaney’s vibrant take on the personal disclosures of Hollywood luminaries. Joe Davidson memorializes a life lived through concrete castings of the insides of his own shoes, while Kathryn Hart reveals her personal form of survivor guilt with a sculpture that includes found bone, which she refers to as a private confessional.

Dani Dodge, who was raised agnostic but has spent much of her life exploring different faiths, previously did a performance piece taking confessions and giving twisted penance at an LA Pride Festival.

“You have to wonder how the religious and secular populations reflect on, illustrate and purge themselves of guilt when confession is reduced to hashtags on social media.” Dodge said. “When Alanna and I put together this show with various takes on confessionals, and figurative works that drill into the heart of our guilt and fear, we wanted to address the abundance of guilt by attempting to satiate the audience’s appetite for repentance.”

Ser100x100_c.jpg)