Wall of Martyrs

- May 28, 2021 09:53

PARIS, 1871 — In the aftermath of the Prussian invasion of France, and the collapse of the Second Empire, two rival governments arise.

One of them is the Paris Commune. Its headquarters: the city streets, the blazing foundry of radical democracy. The defense of the Paris Commune will depend on its citizens, the soliders of the National Guard.

The other government is based in Versailles. Its headquarters: the old seat of royal power, that infamous abode of aristocrats. Its leadership is dominated by monarchists and reactionaries, openly collaborating with occupying Prussian forces.

In early spring, civil war erupts. What triggers the fighting, according to the teacher and dedicated Communard, Louise Michel, is the seizure of the National Guard’s artillery:

The cannon paid for by the National Guard had been left on some vacant land in the middle of the zone abandoned by the Prussians. Paris objected to that, and the cannon were taken to the Parc Wagram. The idea was in the air that each battalion should recapture its own cannon. A battalion of the National Guard from the Sixth Arrondisement gave us our impetus. With the flag in front, men and women and children hauled the cannon by hand down the boulevards, and although the cannon were loaded, no accidents occurred. Montmartre, like Belleville and Batignolles, had its own cannon. Those that had been placed in the Place des Vosages were moved to the faubourg Saint Antoine. Some sailors proposed our recapturing the Prussian-occupied forts around the city by boarding them like ships, and this idea intoxicated us…

Then before dawn on March 18 the Versailles reactionaries sent in troops to seize the cannon now held by the National Guard. One of the points they moved toward was the Butte of Montmartre, where our cannon had been taken. The soldiers of the reactionaries captured our artillery by surprise, but they were unable to take them away as they had intended, because they had neglected to bring horses with them.

Learning that the Versailles soldiers were trying to seize the cannon, men and women of Montmartre swarmed up the Butte in a surprise maneuver. Those people who were climbing believed they would die, but they were prepared to pay the price.

The Butte of Montmartre was bathed in the first light of day, through which things were glimpsed as if they were hidden behind a thin veil of water. Gradually the crowd increased. The other districts of Paris, hearing of the events taking place on the Butte of Montmartre, came to our assistance.

The women of Paris covered the cannon with their bodies. When their officers ordered the soldiers to fire, the men refused. The same army that would be used to crush Paris two months later decided now that it did not want to be an accomplice of the reaction. They gave up their attempt to seize the cannon from the National Guard. They understood that the people were defending the Republic by defending the arms that royalists and imperialists would have turned on Paris in agreement with the Prussians. When we had won our victory, I looked around and noticed my poor mother, who had followed me to the Butte of Montmartre, believing I was going to die.

Regathering their forces, the Army of Versailles attacked Paris once again. Now the Commune’s defenders found themselves outnumbered five to one. They had no organized military leadership. They had no plan of defense. There was no one coming to support them from outside.

According to Michel:

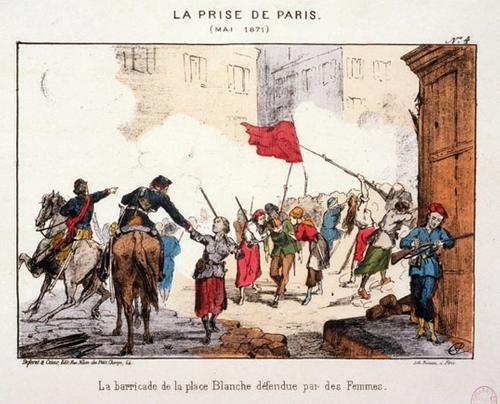

If the reaction had had as many enemies among women as it did among men, the Versailles government would have had a more difficult task subduing us. Our male friends are more susceptible to faintheartedness than we women are. A supposedly weak woman knows better than any man how to say, “It must be done.” She may feel ripped open to her very womb, but she remains unmoved. Without hate, without anger, without pity for herself or others, whether her heart bleeds or not, she can say, “It must be done.” Such were the women of the Commune. During Bloody Week, women erected and defended the barricade at the Place Blanche—and held it till they died…

In my mind I feel the soft darkness of a spring night. It is May 1871, and I see the red reflection of flames. It is Paris afire. That fire is a dawn, and I see it still as I sit here writing…

In the night of May 22 or 23, I believe, we were at the Montmartre cemetery, which we were trying to defend with too few fighters. We had crenelated the walls as best we could, and, except for the battery on the Butte of Montmartre—now in the hands of the reactionaries, and whose fire raked us—and the shells that were coming at regular intervals from the side, where tall houses commanded our defenses, the position wasn’t bad. Shells tore the air, marking time like a clock. It was magnificent in the clear night, where the marble statues on the tombs seemed to be alive.

When I went on reconnaissance it pleased me to walk in the solitude that shells were scouring. In spite of my comrades’ advice, I chose to walk there several times; always the shells arrived too early or too late for me. One shell falling across the trees covered me with flowered branches, which I divided up between two tombs…

In the midst of all this [Polish military officer and fellow Communard] Jaroslav Dombrowski passed in front of us sadly on his way to be killed. “It’s over,” he told me.

“No, no,” I said to him, and he held out both his hands to me.

But he was right.

Three hundred thousand voices had elected the Commune. Fifteen thousand stood up to the clash with the army during Bloody Week…

In May 1871 the streets of Paris were dappled in white as if by apple blossoms in the spring. But no trees had cast down that mantle of white; it was chlorine that covered the corpses. Now, the ground was all white again, this time with snow. On 28 November 1871, six months after the hot-blooded butchery had ended, the cold-blooded assassinations began.

The soldiers had become tired and perhaps their machine guns were breaking down. Now there would be an end to scenes of limbs half-covered with earth, an end to cries of agony coming from heaps of persons who had been summarily executed, an end to swallows dying poisoned by the flies that had been feeding in that enormous charnel house. Henceforth, murder would be done cold-bloodedly, in an orderly fashion.

We do not know the names of all those who died in the hunt and after. The enormous number of missing persons proves how minimal the official figures of the slaughter are. Sometimes now, in the corners of cellars, skeletons are found, and no one knows where they came from. People claim it is mysterious, but every out-of-the-way spot became a charnel house to the victory of the Versailles royalists…

In the summer of 1873 they were still shooting prisoners… After a mockery of a trial in which I made no attempt to defend myself, I was sentenced to deportation...

Like thousands of other Communards, Michel found herself exiled to the South Pacific colony of New Caledonia, where she lived for seven years.

In the aftermath of the Paris Commune, the battle continued—a struggle between the forces of remembering, and the forces of forgetting.

The government’s brutal crackdown failed to deter survivors from making memorials to the martyrs. Each spring, they undertook a pilgrimage, a montée au Mur, a procession to the Montmartre Cemetery, where the Communards had made their final stand.

Each spring, Parisian men, women, and children climbed up the hill to lay wreathes of flowers at the Mur des Fédérés, the “Communards’ Wall,” where so many of them had fallen. Year after year, crowds of Parisians, and others, came to lay their wreathes in silence.

They came in silence only because they were not allowed to speak. In the interest of public order, the government forbade speeches and demonstrations in the presence of the wall. The government also refused to allow a permanent inscription memorializing the defenders of the Paris Commune. Then they relented, and permitted a simple plaque.

In another, later gesture of appeasement, the national government agreed to allow a separate memorial, which would not be located at the site itself, but sculpted into a wall nearby. As required, the memorial would be dedicated not to the Communards but to all “victims of revolutions.”

In 1909, the Monument aux victimes des Révolutions was unveiled. The artist, Paul Moreau-Vauthier, used stones from the original Mur des Fédérés. In the sculpture, he portrays a group of ghostly figures, either emerging from or receding into the wall itself. They seem to hover behind a plaintive female figure, her arms outstretched. Who is she? And for whom does she mourn? To this day, the memorial gives rise to contradictory interpretations.

Red Virgin: Memoirs of Louise Michel

University of Alabama Press

31100x100_c.jpg)