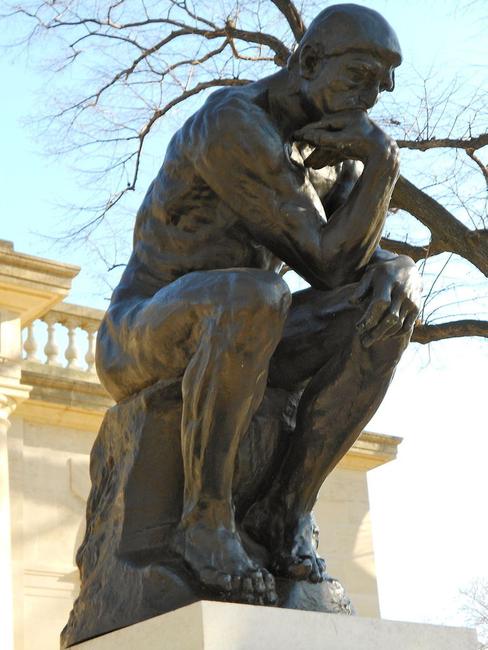

'Rethinking the Modern Monument' at The Rodin Museum

- PHILADELPHIA, Pennsylvania

- /

- February 04, 2019

The Rodin Museum in Philadelphia has reopened with a new installation that explores Auguste Rodin’s innovative, often controversial, approach to the character and function of public monuments. Rethinking the Modern Monument places a number of his designs for sculptures that were intended to be displayed in prominent public spaces, in direct conversation with one another to help us reconsider and reflect upon the form and function of monuments during Auguste Rodin’s time and thereafter.

Rodin chose not to celebrate the subjects—for example, royalty or victorious military leaders—that had long been associated with monumental public sculpture, commemorating instead different subjects such as artists, poets and intellectual figures or giving form to emotions and abstract ideas. The installation features many of the artist’s best-known works and includes sculpture by other modern artists who were inspired by the boldness and realism of Rodin’s designs as well as his iconoclastic approach to the public monument. Varying in size and media, from life-sized statues in bronze to smaller plaster studies, the installation asks questions that remain vital today: what is the proper function of the public monument, what should it look like, and who decides the subject and what form it should take?

Rodin held strong convictions about what a public monument should be. In 1907, he stated his view to the French art critic Paul Gsell: “By convention, a statue in a public place must represent a great man in a theatrical attitude which will cause him to be admired by posterity. But such reasoning is absurd…. There is nothing more beautiful than the absolute truth or real existence.” From the 1870s until his death in 1917, Rodin would design monuments for France during times of major political, social and economic change. Many of these works shocked critics and the public alike.

Rodin’s first commission for a public monument in France was The Gates of Hell (modeled 1880-1917, cast 1926-28), originally intended as the doors of a planned museum of decorative art. A terracotta model on view shows that Rodin almost immediately deviated from the program he had been given for this work, transforming these doors in the process into a complex and dramatic sculpture on which he would work for the rest of his life. In a nearby gallery, Rodin’s animated design for Scene from the French Revolution (modeled in wax around 1879) is shown as an example of a commission he pursued but never realized. It was intended for a monument in Paris that would have commemorated the creation of the French Republic.

Another gallery contains various studies for the figure of the renowned French writer Honoré de Balzac (1799-1850), demonstrating Rodin’s deep engagement throughout the 1890s with creating a powerful monument to this celebrated literary figure. While Rodin’s initial interest was to portray the writer in a realistic manner, it soon evolved into an ambitious effort to express the essence of Balzac’s genius. When the sculpture was presented to the public in 1898 it was severely criticized. Many years later, Rodin’s bronze monument of Balzac was erected in Paris on the boulevard Raspail, near the corner of the boulevard Montparnasse. A small-scale bronze version of the monument is on view in the galleries.

Modern works by other European sculptors show how the debate over the nature and purpose of public monuments continued long after Rodin’s death, especially during periods of social tumult and change. The installation includes bronze sculptures by Jean Arp, Barbara Hepworth, Jacques Lipchitz, Marino Marini, Chana Orloff, and Alberto Giacometti, among others, displayed alongside Rodin’s work. Picasso’s Man with a Lamb (1943) is highlighted as an example of a statue that Picasso initially believed was not symbolic in meaning or conveyed a specific message but that reflected Rodin’s preference for expressiveness in sculpture. Later, Picasso gave another bronze cast of the work to the French city of Vallauris, where it has since been interpreted as a war memorial commemorating those who fought fascism.

The focus on monuments is reflected both inside and outside the museum’s walls. In addition to Rodin’s Gates of Hell on the portico, other public works include Burghers of Calais (modeled 1884–95, cast 1919–21), made to commemorate the heroism of six leading citizens of the French port of Calais, who offered their own lives to King Edward III of England when he laid siege to the city in 1346 in exchange for the guarantee of the safety of its inhabitants. On Kelly Drive near the Philadelphia Museum of Art is a version of Emmanuel Frémiet’s heroic Joan of Arc (c. 1874), a statue which came to Philadelphia in 1890 when it was purchased by the Fairmount Park Art Association (now the Association for Public Art) on behalf of the city’s French community and as a symbol of France’s historic friendship with the United States. Frémiet’s small-scale version of this monument is on view in the Rodin Museum galleries as well as Rodin’s more anguished study for an unrealized monument to the great French heroine, Joan of Arc, who lost her life defending France against the English during the Hundred Years’ War.

The exhibition is organized by Alexander Kauffman, Andrew W. Mellon–Anne d’Harnoncourt Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow. An audio guide features the voice of Kauffman and photos of the different locales across France where many of Rodin’s public monuments stand today. Kauffman said: “This installation aims to expand upon the idea of the modern monument. Through exploring Rodin’s history and models for monuments this display can spark connections to the ongoing conversation about new approaches and meanings to monuments today.”

Curator

Alexander Kauffman, Andrew W. Mellon–Anne d’Harnoncourt Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow

__Night_Shadows__192100x100_c.jpg)