Last Chance to View Jacob Lawrence's Striking Narratives at the Museum of Modern Art

- August 15, 2015 13:54

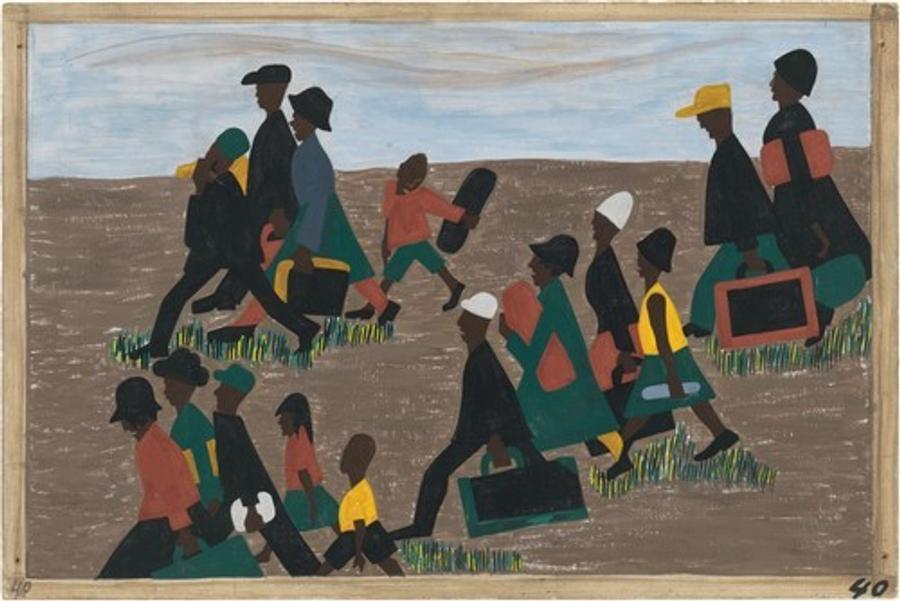

The Museum of Modern Art did a wonderful job with the Jacob Lawrence One-Way Ticket show (on view through Sept. 7, 2015). They are presenting the entire 60 panels of The Migration Series, 1940-41 (made when Lawrence was 23). Shown in one room, the tempera drawings on hardboard panels are single-spaced in clockwise order, all in simple wood frames. Clearly modernist in style, they were conceived as a narrative at the very time that the New York art world was moving away from storytelling.

Born in Atlantic City, NJ, and raised in Harlem, New York City, Lawrence (1917-2000) researched his subject with the help of his future wife, the artist Gwendolyn Knight. He went into amazing detail in both the pictures and the captions, using the First World War as his jumping off point. He analyzed the recruitment by agents for factories -- especially steel mills, and the use of railroads for transportation but also source of jobs leading to one of the first Black labor unions -- the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, in spite of opposition from the Pullman Company. The travels costs were usually paid by employers to be re-reimbursed from future pay envelopes.

Lawrence drew scenes that referenced lynching and law enforcement, as well as floods and insect infestations that had drastic effects on farming. He noted the North was NOT free of racism, and that women laborers and Black professionals such as doctors were along the last to make the transition. He considered the emotional toll of families now in crowded urban conditions and the lonely relatives in small southern towns that they had left behind. Improved childhood education was an important motivation, but the anxiety of the children is nearly palpable. He even discussed, with touching sympathy, the plight of communities emptied of their labor forces. His own parents, from South Carolina and Virginia, were part of this great shift north that really ended only in the 1970s, so this saga was personal.

In the hallway leading to the show there’s a timeline showing the increase of African Americans from tens of thousands in the teens to hundreds of thousands over just a few decades. Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit, and especially New York City, were the primary beneficiaries.

Lawrence achieved such mastery that while the works form a unified cycle, each individual piece can stand alone. The Migration Series was first shown by Edith Halpert at her Downtown Gallery, NYC, in 1942, and subsequently went on a two-year national tour. The Museum of Modern Art and the Phillips Collection acquired half each. In what must have seemed like a flash, Lawrence’s career was established. In 1944, while in the Coast Guard, he had a one-man show at the Museum of Modern Art.

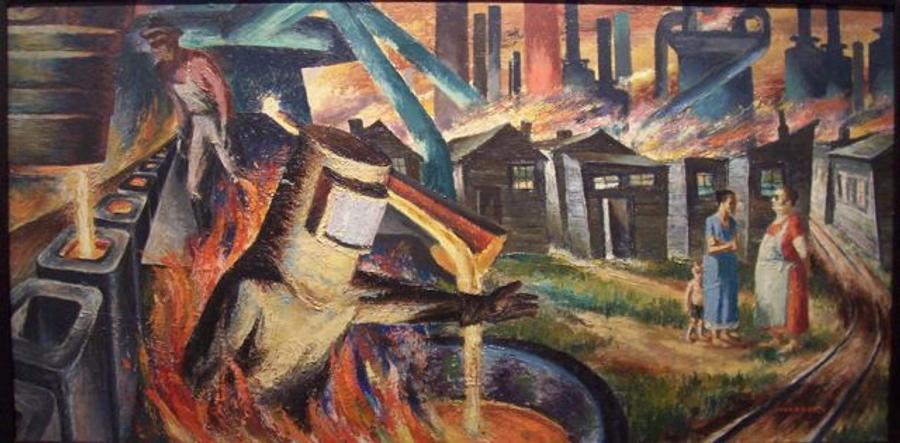

In this show dealing with the “Great Movement North,” MoMA included related photographs with several of Arkansas and Tennessee by Ben Shahn, additional works by Lawrence and African-American colleagues, and an extensive collection of publications, largely books of the period with their amazing covers. Music and historical and sociological information enrich the experience as well. Shown here is Harry Sternberg’s Steel, 1937-38. It just wasn’t in me to use his Southern Holiday. Even Lawrence wasn’t that literal.

__2270x400_c.jpg)