Crocker Art Museum to Celebrate Wayne Thiebaud's 100th Birthday With a Huge Retrospective Next Fall, Travels in 2021

- February 27, 2020 22:40

“It’s just very, very familiar. They’re mostly painted from memory, from memories of bakeries and restaurants — there’s a lot of yearning.” —Wayne Thiebaud

The Crocker Art Museum will debut Wayne Thiebaud 100: Paintings, Prints, and Drawings, an extensive, celebratory retrospective presenting the full range of the Sacramento artist’s achievements on canvas and on paper in an exhibition on view at the Crocker from October 11, 2020 to January 3, 2021.

Opening shortly before Thiebaud’s 100th birthday, the career-spanning exhibition of 100 objects made over more than 70 years (1947-2019), is the largest survey of Wayne Thiebaud’s work in in two decades. Works drawn from the Crocker’s holdings and the collection of the Thiebaud Family and Foundation, many of which have never been shown publicly, as well as the artist’s newest body of work, circus clowns, reveal an extraordinary, expansive practice. Accompanied by a full-color, richly illustrated publication with fresh scholarship by Crocker Art Museum’s Associate Director & Chief Curator Scott A. Shields and others asserts that Thiebaud’s body of work is singular and visionary, informed by memory, tradition, and imagination.

“Wayne Thiebaud is a national treasure, Sacramento is his hometown, and we are delighted to celebrate his 100th birthday in the artist’s home of Sacramento with an exhibition that honors the vitality, vibrancy, and wit of his art and civically engaged life,” says Lial A. Jones, the Museum’s Mort and Marcy Friedman Director & CEO. “Wayne Thiebaud 100 continues a Crocker tradition of organizing an exhibition of the artist’s work in every decade since 1951, when the Crocker accorded him his first solo museum show. We will further recognize his achievements though an important publication, public programs, and community events.”

“Wayne Thiebaud has a reverence for painting and tradition. His art is deeply felt,” says Shields. “His canvases are some of the most important paintings ever made in California, and they possess an enduring interest, combining nostalgia and optimism, loneliness and isolation.”

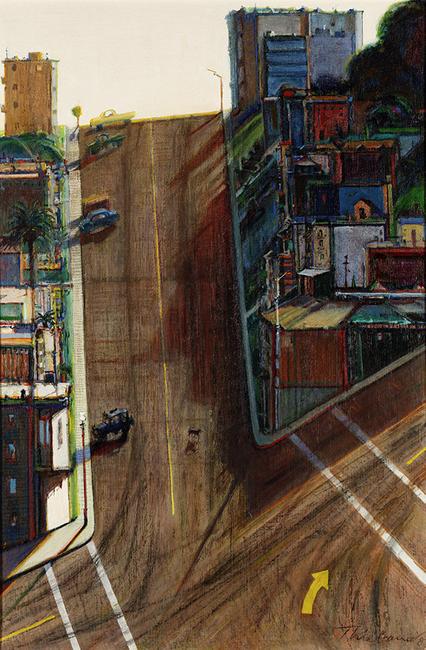

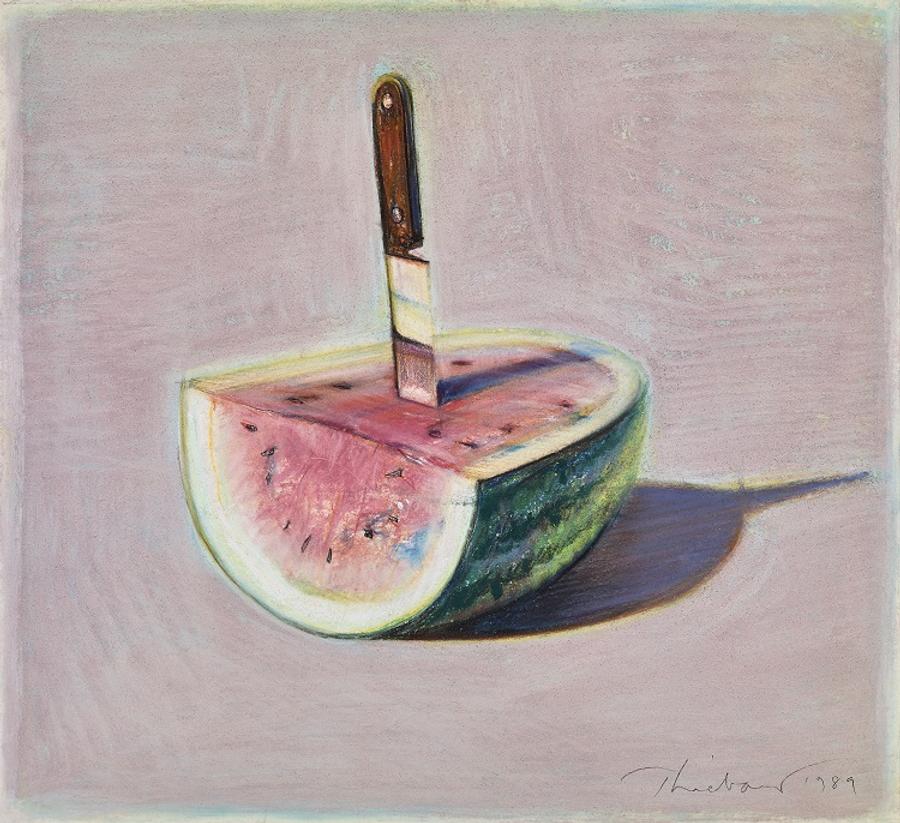

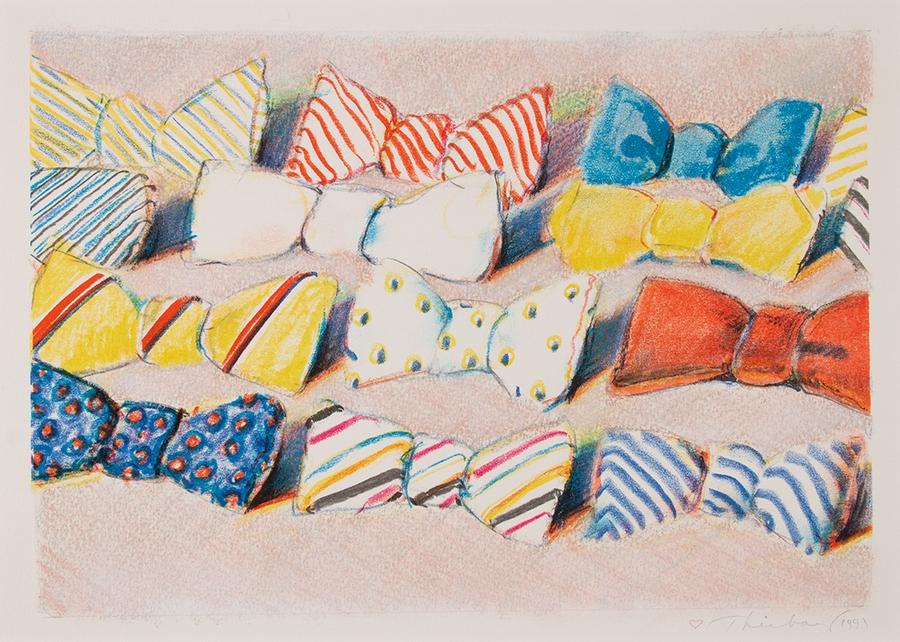

Wayne Thiebaud (b. 1920) was raised in California and is today one of America’s greatest and most admired living artists. Appreciated for creating “a world of longing — a serene abundance that is always a windowpane away,” as Adam Gopnik of The New Yorker has stated, Thiebaud is a recipient of the National Medal of Arts (1994) and the Gold Medal for Painting from the American Academy of Arts and Letters (2017). He made his reputation in the early 1960s with still lifes of comforting, ubiquitous foods, the type served at snack counters, cafeterias, and middle-class diners, such as pies and cakes, ice cream cones, lollipops, and other delectables painted with thick impasto, which at the same time evokes simpler times and places. By the mid-1960s, Thiebaud turned to the figure and then landscape and, in the 1970s, gained new recognition for his dramatic, vertiginous interpretations of the San Francisco cityscape. Many of these same qualities are exemplified in the artist’s sweeping, bird’s-eye portrayals of Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta scenes, a group of paintings he started in the mid-1990s.

This exhibition of 100 objects in every medium and from every period of the artist’s practice spans the scope of his accomplishments in, as Shields asserts, “the redefinition of ordinary things or actions though scale, color, space, and light.” Wayne Thiebaud 100 provides a new appreciation of the artist’s subtle humor and technical accomplishment for those who have long enjoyed his work and those new to his art. Early works in the exhibition illustrate Thiebaud’s rapid evolution, such as The Sea Rolls In (1958), a gestural, energetic, Abstract Expressionist-inspired canvas acquired by the Crocker that same year, and his 1961 Cold Cereal, a decidedly representational work with controlled, eloquent brushwork. Two Seated Figures (1965) is a striking, life-sized painting made during a period when the artist produced “challenging” human still lifes, and Sliced Circle (1986), an oil on paper, evidences his mastery of volumetric form and shadow.

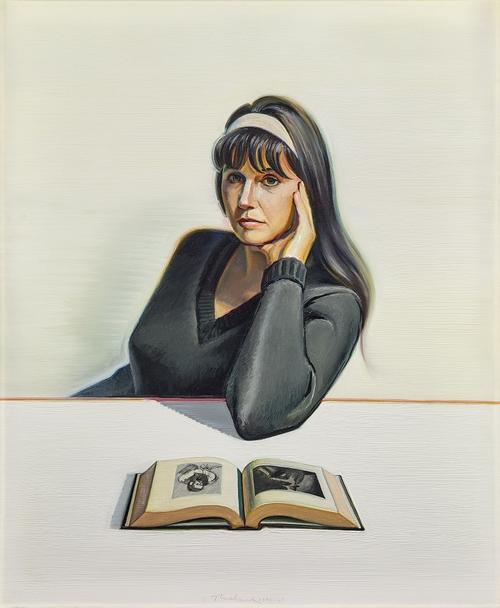

Wayne Thiebaud 100 includes triumphs of the artist’s oil paintings drawn from the Crocker’s permanent collection, which demonstrate his signature, fool-the-eye brushwork that takes on the character of what it depicts. These works include the whipped-to-perfection meringues and creamy custards of Pies, Pies, Pies (1961) and Boston Cremes (1962). Others from the Museum’s collection were personally gifted by the artist and his family, such as the iconic Betty Jean Thiebaud and Book (1965-1969) and Street and Shadow, a dizzying canvas made during Thiebaud’s period of interest in the verticality of San Francisco’s plunging streets. The exhibition concludes with the artist’s return to the figure. Bumping Clowns (2016) is a buoyant, joyful, oil on linen that radiates an American nostalgia, a “culmination of what Thiebaud has been doing all along — caricaturing what he sees,” says Shields.

The retrospective also features Thiebaud’s adventuresome work in printmaking, ranging from his 1964 series Delights (Crown Point Press, 1965), which includes Double Deckers, Gum Machine, and Lemon Meringue, to later prints of various subjects with handwork in watercolor and pastel. An array of other works on paper attest to the artist’s skills as a draftsman and watercolorist. Storyboard-like sketches in ink and watercolor depict small figures, foods, and even landscapes, animating the process and working habits of the artist.

Wayne Thiebaud and Sacramento

Much of what has made the artist what he is today can be traced to Sacramento, and Wayne Thiebaud 100 presents a substantial body of work that establishes an intimate record of the artist’s engagement with the region, which the artist himself acknowledges “gave me something essential.”

According to Shields, Thiebaud first came to know “the light, heat, agriculture, and middle-American ambiance” of Sacramento in 1942, when the artist was stationed at Mather Air Force Base and served as a graphic artist and cartoonist. He returned to Sacramento in 1950. As Thiebaud recalls, it “was still a very American place with its old cafeterias, streetcars, people dressed up ... I looked for things that I thought were sort of anonymous. Pies, and particularly pie-cases; displays.” He began making a lifetime of regular visits to the Crocker, seeing early, key works of California art that would inform some of his later depictions of cliffs, city scenes, and smorgasbords.

An active and engaged Sacramentan, Thiebaud designed and directed the annual art exhibitions for the California State Fair, he earned his master’s degree at Sacramento State College, and he taught at Sacramento Junior College, later becoming chair of the art department. He received an important commission from the Sacramento Municipal Utility District to create a mosaic mural, Water City, for the exterior of its headquarters building, wrapping the ground floor. Later, the artist’s sweeping representations of water, levees, and farmland in his Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta scenes, depict “the landscape as it is felt.” Inspiration came out of Thiebaud “driving around and looking,” and from his interest in the “river as the lifeblood” of agriculture.

“A Joy of Painting, a Joy of Life”

The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated scholarly catalogue with essays by Shields; Julia Friedman, art writer and curator; Margaretta M. Lovell, Jay D. McEvoy Chair and Professor of the History of American Art, University of California, Berkeley; and Hearne Pardee, Professor of Art, University of California, Davis. Mary Okin, Ph.D. candidate, University of California, Santa Barbara, contributed a chronology.

In scholarly essays, Shields vividly chronicles Thiebaud’s artistic journey and influences, from the artist’s adolescence in Long Beach, serving up stacked ice cream cones, hot dogs, and pie; to his apprenticeship at Walt Disney Studios; his work as an usher at movie theaters filled with candy, soda, and popcorn; and his early interest in masters such as Piet Mondrian, Edgar Degas, and Henri Matisse.

Shields further animates the impact that other artists and movements had on Thiebaud’s outlook and approach, and his use of new strategies: Paul Cézanne’s cones, cubes, cylinders, and spheres in food; a “beautiful direct encounter” with the work of Richard Diebenkorn; his use of volume and shadow in the 1960s; the vanishing points of Surrealism and perspectives used in Asian art; and George Herriman’s comic strip Krazy Kat, to name a few.

In his revelatory and incisive “This is Not a Pie,” a new and significant contribution to the study and understanding of the artist, Shields remarks on the artist’s wit and the “unreality” of his work. He asserts that Thiebaud lures viewers “into believing that what he presents is real,” delving into the less-frequently acknowledged influence of René Magritte, “whose own iconic placement of everyday objects against spare background are compelling forerunners for Thiebaud.” Shields considers the impact of the artist’s hero Willem de Kooning, as well as techniques arising from masters Thiebaud admired, including the painter Diego Velázquez, the American portraitist John Singer Sargent, and the Spanish Impressionist Joaquín Sorolla. Shields further asserts that Thiebaud’s fully realized three-dimensionality and optimistic, handmade approach was distinct and separate from Pop artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein, and he enthuses that the artist has updated the tradition of trompe-l’oeil, and reinvestigated the concept of synesthesia, “wherein one sense evokes another.”

In 2021, Wayne Thiebaud 100 travels to the Toledo Museum of Art, OH; the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis, TN; the McNay Art Museum in San Antonio, TX; and Brandywine Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, PA.

_-3100x100_c.jpg)

100x100_c.jpg)