Reynolda House Museum Acquires Works by John Singer Sargent and Minnie Evans

- January 25, 2022 16:52

Reynolda House Museum of American Art has announced that Mr. and Mrs. Leslie Baker of Winston-Salem have offered the Museum a portrait of Mrs. Augustus Hemenway by acclaimed portrait artist John Singer Sargent and an untitled drawing by the self-taught African American artist from North Carolina, Minnie Evans.

“We wanted to ensure these gifts would be in a place where they could serve the widest possible audience, and Reynolda House is extremely committed to strengthening the community through its educational mission,” said the Bakers. “We are excited that the works by Minnie Evans and John Singer Sargent will be used as teaching tools for generations to come.”

Sargent’s portrait of Harriet Hemenway will join another painting by the artist at Reynolda—his portrait of the Marchesa Laura Spinola Núñez del Castillo from 1903 is on long-term loan from Museum founder Barbara Babcock Millhouse.

“I am thrilled that the portrait of Harriet Hemenway will continue to inspire at Reynolda,” said Millhouse. “John Singer Sargent’s portrayal of Hemenway can be classified as among his absolute best.”

The most popular portrait painter of the Gilded Age, John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) described himself as “a man of prodigious talent.” Painting in Paris, London, New York and Boston, Sargent was known to invest in his subjects with elegance, vitality and keen psychological insights.

Mrs. Augustus Hemenway, or Harriet Hemenway, was a prominent woman in Boston society, known primarily as the founder of the Massachusetts Audubon Society. Harriet’s actions stemmed from her horror at the practice of killing birds for their feathers, which were used to decorate women’s hats. According to John H. Mitchell, writing in Sanctuary: The Journal of the Massachusetts Audubon Society, “One of the seminal events in the history of activism in this country took place in a parlor in Boston’s Back Bay in 1896. On a January afternoon, that year, one of the scions of Boston society, Mrs. Harriet Lawrence Hemenway, happened to read an article that described in graphic detail the aftereffects of a plume hunter’s rampage—dead, skinned birds everywhere on the ground …. She carried the article across Clarendon Street to her cousin Minna B. Hall. There, over tea, they began to plot a strategy to put a halt to the cruel slaughter of birds for their feathers.” The result was the Massachusetts Audubon Society, which led to the foundation of the National Audubon Society.

According to the sitter’s granddaughter, Augustus Hemenway asked his wife to commission a portrait from Sargent when the artist was visiting Boston. After offering her children as subjects, Harriet agreed to sit for the artist at his request. Sargent disguised Harriet’s pregnancy in the folds of her black dress and behind the elegant gesture of her hands holding a flower. Harriet’s granddaughter Elvine recalled, “When the head seemed finished, he asked her to put her hands in some interesting way, and as they were trying various positions, he saw a vase of white flowers in the room and gave her one to hold.” Mitchell stated that the flower was a water lily, which was “symbolic language proclaiming her condition [of pregnancy], and a rare, even shocking public announcement for the period.”

In 1916, the portrait of Harriet Hemenway was exhibited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. W.H. Downes, writing in the Boston Evening Transcript, praised the “brilliant, vital, vivid, and animated portrait of Mrs. Hemenway, also dated 1890. [It] is especially remarkable for the rich, glowing, transparent flesh tones, so handsomely contrasted with the fine tone of the black dress. The expression is that of a splendidly alive, normal, wholesome personality whose wide-open eyes look out with boldness, courage, and confidence upon a world that is well-worth living in.”

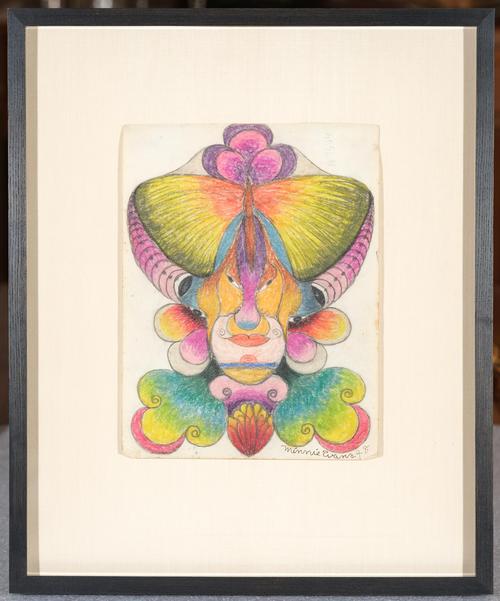

Born in Long Creek, North Carolina, Minnie Evans (1892-1987) was a self-taught African American artist. She began drawing in middle age, and attributed her compulsion to make art to divine inspiration. Her work is known to be characterized by an emphatic symmetry, vivid colors and imagery that combines human faces and natural forms.

Of her work, Evans said, “This has come to me, this art that I have put out, from nations that I suppose might have been destroyed before the flood. No one knows anything about them, but God has given it to me to bring them back into the world.”

Scholars attribute Evans’s frequent use of plant forms in her drawings to her employment as a gate attendant at Airlie Gardens in Wilmington, North Carolina. She said, “Sometimes I want to get off in the garden to talk with God. I have the blooms, and when the blooms are gone, I love to watch the green. God dressed the world in green.”

Her drawing depicts a mythical creature with eyes, a nose and a mouth located on a strong central axis. The top of the figure’s head resembles a butterfly, and petal-like forms sprout from the head and neck. Below the figure’s mouth, a sun sets above a blue and green sea on the creature’s chin. Green forms marked by scrolling black lines occupy the figure’s shoulders, while a red-orange and yellow flower blooms in the center bottom portion of the drawing. The effect is mysterious and otherworldly, a product of the artist’s dreams.

Works of art by Evans are included in the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Museum of Modern Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The Museum’s new acquisition by Evans was sold to Bud Baker by the St. John’s Museum, now the Cameron Art Museum, in Wilmington. When it enters Reynolda’s collection, it will join other pieces by self-taught Black artists, such as Horace Pippin’s The Whipping and Thornton Dial’s Crying in the Jungle, Crying for Jobs. It will also increase the Museum’s holdings of work by African American women, currently limited to works by Betye Saar and Lorna Simpson.

Executive Director Allison Perkins adds, “The gift of this drawing by visionary artist Minnie Evans is an incredible addition to Reynolda’s rich American art holdings and strengthens the institution’s strategic efforts toward increasing the representation of historically underrepresented groups—African Americans and women—in our collection.”

The works will be on view in the library of the historic house beginning February 15.

Reynolda House, located at 2250 Reynolda Rd., Winston-Salem, N.C., opens to the public on Feb. 1 with a new season of programs and exhibitions, including Black Is Beautiful: The Photography of Kwame Brathwaite. Learn more at reynolda.org.

100x100_c.jpg)

![Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640), After Titian (Tiziano Vecelli) (Italian [Venetian], c. 1488–1576), Rape of Europa, 1628–29. Oil on canvas, 71 7/8 x 79 3/8 in. Peter Paul Rubens (Flemish, 1577–1640), After Titian (Tiziano Vecelli) (Italian [Venetian], c. 1488–1576), Rape of Europa, 1628–29. Oil on canvas, 71 7/8 x 79 3/8 in.](/images/c/e2/2e/Jan20_Rape_of_Europa100x100_c.jpg)