'Queen Nefertari’s Egypt' Exhibition Brings Egyptian Masterpieces to New Orleans

- February 06, 2022 14:43

The New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA) presents Queen Nefertari’s Egypt, on view March 18–July 17, 2022. As the favorite wife of Pharaoh Ramesses II (reigned 1279–13 BCE), Queen Nefertari had significant diplomatic and religious roles before her death in c. 1250 BCE, and she is linked to some of the most magnificent monuments of ancient Egypt. Artifacts presented in Queen Nefertari’s Egypt provide an extensive look into the power and influence of women during the New Kingdom period (c. 1539-1075 BCE), when Egyptian civilization was at its height.

“The exceptional objects in Queen Nefertari’s Egypt, drawn from the collection of the Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy, will bring to life the fascinating history and culture of ancient Egypt,” said Susan Taylor, Montine McDaniel Freeman Director. “NOMA is delighted to be able to present exceedingly rare objects found within the tomb of Nefertari herself in an installation where visitors can appreciate their great history up close.”

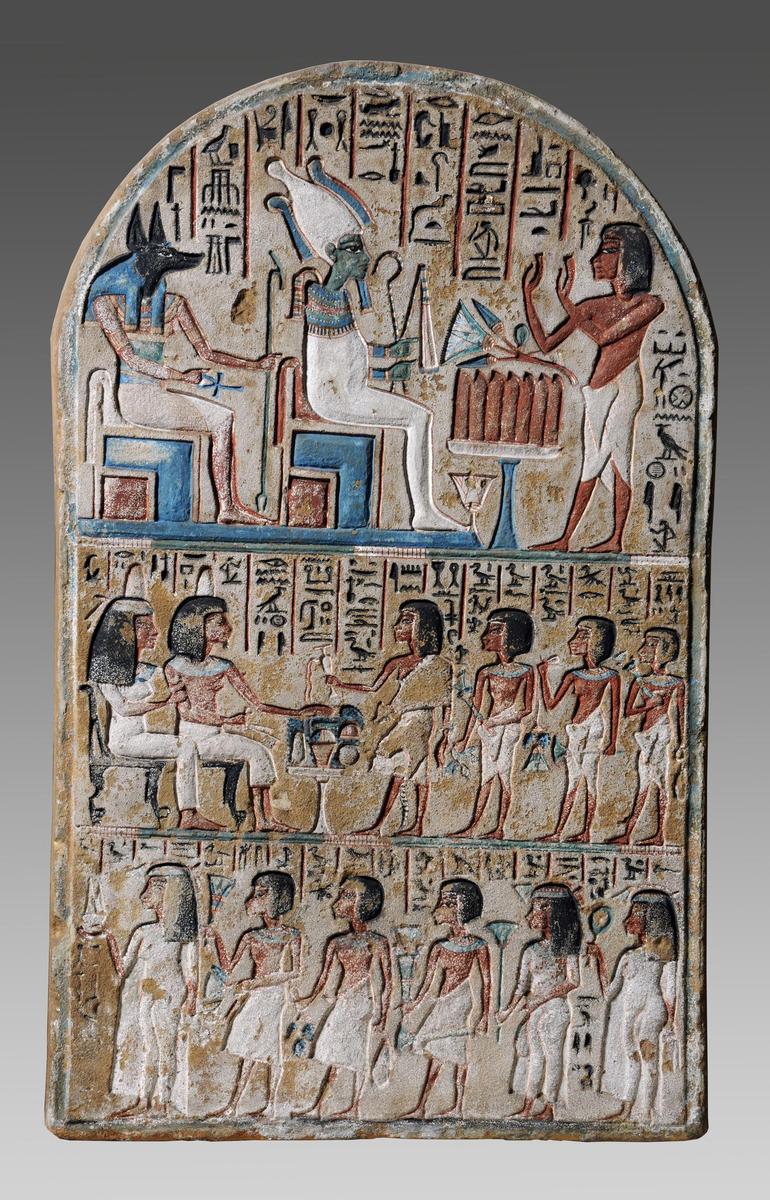

Nefertari served not only as a queen, but as a divine consort, diplomat, and queen mother, and had one of the largest and most richly decorated tombs in the Valley of the Queens. Through the presentation of 230 objects in the exhibition, the role and legacy of women, including Nefertari, and other great royal wives, sisters, daughters and mothers of pharaohs, as well as goddesses, are brought to life through sculpture, objects, votive steles, stone sarcophagi, and painted coffins, as well as items of daily life from the artisan village of Deir el-Medina, home to the craftsmen who built royal tombs.

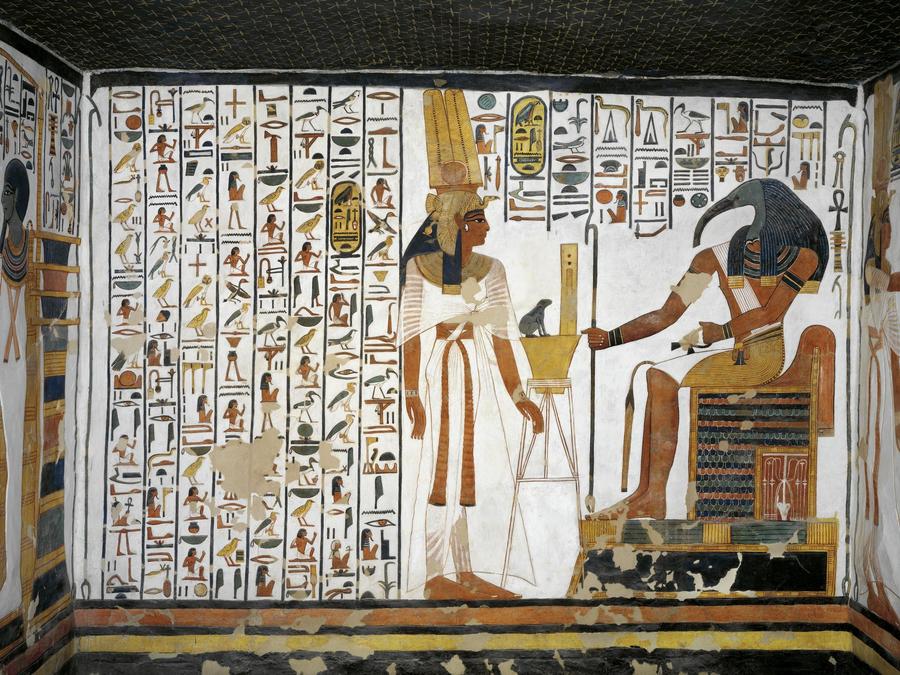

Until the early 1900s, Nefertari, whose name means “beautiful companion” and who was called “the one for whom the sun shines,” was known primarily through a few sculptures, hieroglyphic inscriptions, and text-based sources related to Ramesses II. In 1904, the Italian archaeologist Ernesto Schiaparelli, then director of the Museo Egizio, first re-discovered her tomb. Although the contents had been looted in ancient times, the remaining objects and the magnificent murals lining the tomb walls revealed the power, authority, and status of Nefertari, and detailed the perilous journey she had to make on her path to immortality.

“Through the presentation of this exhibition, we hope to ignite the same sense of wonder that was sparked with NOMA’s 1977 exhibition Treasures of Tutankhamun, which visitors still reminisce about to this day,” said Taylor. “We look forward to welcoming long-time enthusiasts of this fascinating subject matter, as well as introducing the treasures of ancient Egypt to new generations of locals and visitors alike.”

Featured Themes

Presented in six sweeping sections, Queen Nefertari’s Egypt casts light upon the belief systems of the New Kingdom period, life in the women's palace and the roles of women in ancient Egypt, as well as the everyday life of artisans, and the ritual practices around death and the afterlife.

Pharaohs, Goddesses, and the Temple

The ruler of ancient Egypt was known as the pharaoh, a title and position inherited by birth. The pharaoh served as the empire’s spiritual, judicial, and political leader. While living, the pharaoh was considered the incarnation of Horus, son of the sun god Ra, temporarily dwelling among mortals. Death would transform the pharaoh into a full god, but while on Earth, he was charged with maintaining justice, truth, order, and cosmic balance.

Religion suffused every aspect of life in ancient Egypt. Egyptians appealed to their pantheon of deities through various rituals, ceremonies, and celebrations, and built elaborate temples dedicated to the gods where daily offerings were made. In exchange, they believed that the gods would grant life, health, and strength to the land and its people.

Egypt’s queens played an important role in religious processions and celebrations, representing the female aspect of the divine on Earth. Throughout her reign, Nefertari served as an officiant and participant in numerous religious rites, evidence of which may be found in inscriptions and paintings on temples, tombs, and monuments.

Women in Ancient Egypt

From predynastic times, the pharaohs of ancient Egypt married multiple wives to emphasize their wealth, facilitate diplomatic alliances, and ensure their line of succession. The pharaoh’s many wives and other dependents of all ranks—his mother, sisters, aunts, and children, along with their servants and attendants—lived together in a harem, or women’s palace.

During the New Kingdom, these palaces were economically independent communities. The richness of life in the palaces is reflected in the objects presented in Queen Nefertari’s Egypt, including representations of goddesses and queens, articles of beauty and adornment, and musical instruments.

Deir el-Medina: The Worker’s Village

Deir el-Medina was a planned community for the workers who constructed and decorated the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings and the Valley of the Queens. It is believed that Amenhotep I (c. 1541-1520 BCE) first planned the site, which was continually occupied until the collapse of the New Kingdom in 1069 BCE.

The residents included masons, draftsmen, painters, and other craftsmen, as well as scribes, administrators, and service workers, such as washermen and midwives. Preserved tools, sacred objects, and other artifacts uncovered at Deir el-Medina provide a glimpse into the way ordinary people lived and died in this ancient land.

The Afterlife

Ancient Egyptians believed that life continued after death in the afterlife. To ensure they reached spiritual paradise, they developed an elaborate set of funerary beliefs and practices. When a person died, their body was carefully preserved through the process of mummification. The body was placed inside a coffin, which was placed inside a tomb filled with provisions for the afterlife.

The spirit of the deceased embarked on a journey through the underworld, a dangerous realm overseen by Osiris, its lord and ruler. The spirit had to complete certain tasks to pass through the halls of Osiris and reach the afterlife. The deceased was aided in these tasks by funerary texts like the Book of the Dead. In the afterlife, the spirit was reunited with the body, and life continued in perpetual bliss.

Queen Nefertari's Tomb

Queen Nefertari’s tomb was constructed around 1250 BCE, at the height of New Kingdom craftmanship. Pharaoh Ramesses II had the large and elaborately decorated “house of eternity” tunneled into the Theban Necropolis for his most beloved Great Royal Wife, Nefertari.

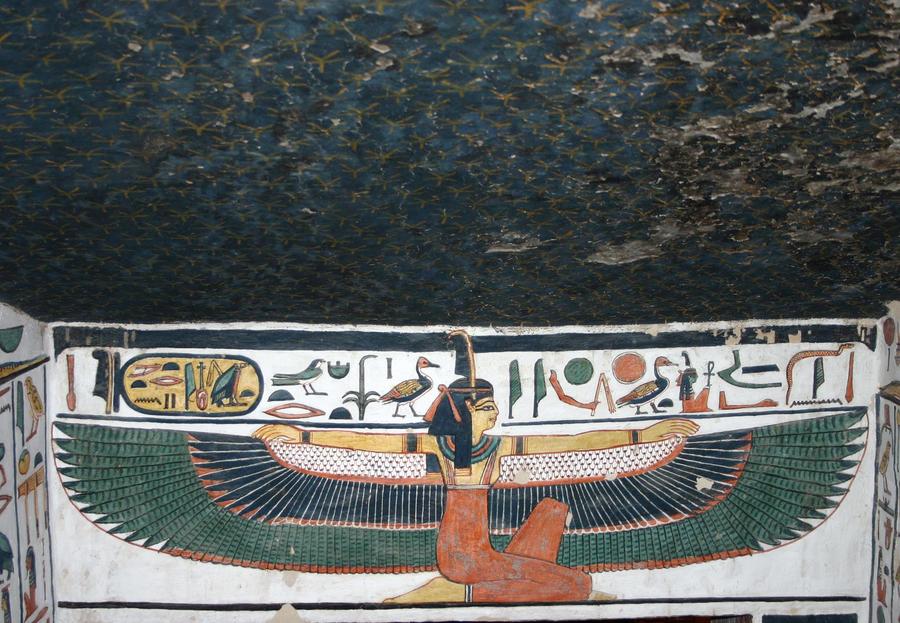

The tomb consists of two primary parts: the upper antechambers and the lower burial chamber, connected by two descending staircases. The structure of the tomb was meant to evoke the convoluted path that the deceased had to follow to reach the afterlife. The vivid wall paintings represent elements of the spiritual journey that the Queen’s spirit would have made through the underworld in order to finally rest with the god Osiris.

Egyptian Funerary Texts and Painted Coffins

Funerary books provided guidance for the dead to reach the afterlife safely. These texts supplied spells or utterances that would help the deceased negate threats and overcome obstacles on the long and perilous journey through the underworld.

While the Book of the Dead is the most well-known Egyptian funerary text, several other texts, known collectively as the Books of the Underworld, were also used. These books follow the voyage of the sun god through the netherworld during the 12 hours of night, until his successful rebirth the next morning. Although described as books, the spells were written and lavishly illustrated on papyri, coffins, and tomb walls as well as decorated amulets and shabtis.

The final gallery contains a number of painted coffins, made to protect the mummified body of the deceased. Of anthropoid (human) form, the features of the deceased were sculpted or painted onto the lids.

Nefertari’s Tomb Model

Situated outside of the galleries, visitors will be able to see an early 20th century model of Nefertari’s tomb. Made to scale and finely detailed, the model is so accurate that it provided information for conservators working on the restoration of the tomb murals in the 1980s and 1990s, undertaken by the Getty Conservation Institute.

Exhibition Catalogue

The Queen Nefertari’s Egypt catalogue, available at the NOMA Museum Shop in March, features nine essays by distinguished scholars such as Dr. Christian Greco, director of the Museo Egizio. Essays focus on Egyptian funerary beliefs, various aspects of the Museo Egizio’s outstanding collection, the early twentieth-century Italian archaeological missions, and Schiaparelli’s most important find—the tomb of Queen Nefertari. The catalogue also includes a beautifully illustrated selection of more than 70 of the 230 exceptional objects featured in the exhibition, which showcase the legacy of Nefertari and other royal women of the New Kingdom period (c. 1539–1075 BCE), illustrate everyday life and death in Deir el-Medina, and provide insight into the remarkable customs and culture of ancient Egypt.

5100x100_c.jpg)