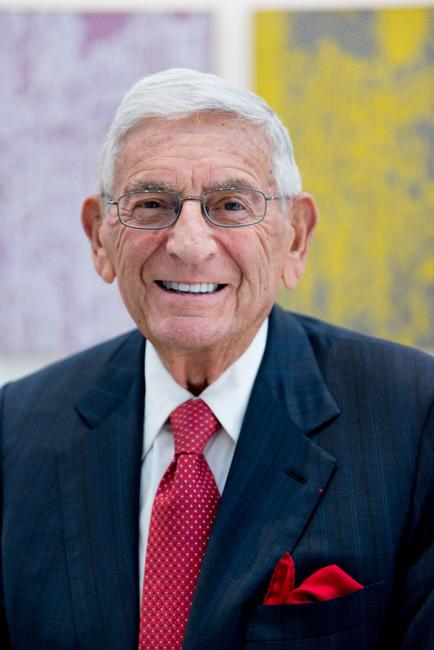

Eli Broad, Billionaire Businessman Who Revitalized L.A. Cultural Scene, Remembered

- May 02, 2021 13:15

Eli Broad (1933-2021), the influential billionaire businessman and philanthropist who poured his fortune into cultural institutions, art collecting, public education, civic improvement and scientific endeavors, died on Friday in Los Angeles. He was 87.

His generous philanthropy, including the $140 million namesake private museum he founded, greatly benefited the Los Angeles region and beyond. Noting his critics along the journey of reshaping business and cultural landscapes, Broad wrote, “I’m not the most popular person in Los Angeles,” in his 2012 memoir “The Art of Being Unreasonable: Lessons in Unconventional Thinking."

Excerpted from the Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation remembrance:

Eli Broad, the first entrepreneur to found two companies in two different industries and build them into Fortune 500 powerhouses, provided first homes to hundreds of thousands of families and secure retirements to millions of Americans throughout his five-decade business career.

His most significant legacy, however, is his philanthropy. As founding members of The Giving Pledge, Eli and his wife of over 60 years, Edye, devoted their multi-billion dollar fortune to advancing more high-quality learning opportunities for K-12 public school students across the country, improving human health, and sharing contemporary art with large audiences. A lifelong entrepreneur and builder, Eli created and grew new businesses, educational organizations, scientific research institutions and museums.

Eli had an uncanny ability to see both opportunities and landmines where others could not. His success in two industries, homebuilding and retirement savings, relied on key insights into his customers. With Kaufman and Broad Home Corporation, now known as KB Home, Eli priced houses affordably to appeal to young families eager to leave apartments for homes—they went on to buy 600,000 of his company’s houses across the country. At SunAmerica—which started as a small life insurance company purchased to diversify Kaufman and Broad’s homebuilding business—Eli recognized that the aging Baby Boomer generation needed retirement savings, rather than just life insurance. His insight made SunAmerica a financial services powerhouse, and the New York Stock Exchange’s fastest growing company of the 1990s.

After leaving the world of business following the sale of SunAmerica to AIG in 1999, Eli pursued a new career as a full-time philanthropist, driven by a strong desire to give back. He and Edye founded and funded numerous institutions in education, science and the arts. Through their foundation, the Broads established two programs to help develop and support public school system leaders and managers, the Broad Academy and the Broad Residency in Urban Education. They funded three stem cell centers in California and they invested more than $1 billion to create and endow the Broad Institute, a globally renowned genomic medicine research center in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Avid contemporary art collectors, they built The Broad, a museum in downtown Los Angeles, to hold their 2,000 artworks—more than 3.5 million people had visited in its first 4.5 years before the Covid-19 pandemic temporarily shut its doors.

Born on June 6, 1933, Eli was the doted-on only child of hard-working parents, both Jewish immigrants from Lithuania who made the South Bronx their home.

After the family moved to Detroit in 1940—which World War II had transformed into a boomtown—Leon opened a five-and-dime store, and Rita kept the books, often working late into the night. Broad delivered newspapers and helped out at the store after school. He also inherited his father’s entrepreneurialism and his mother’s quiet diligence, starting his first business at the age of 13.

A longtime stamp collector, Eli spotted a magazine ad for a sale on stamps—100 of them for $1.95, available at Chrysler International in downtown Detroit. Broad put on a double-breasted sport coat and took a streetcar to the automaker, unchaperoned. He was the only person inquiring about the stamps. After returning home with his haul, he began placing ads for individual stamps in collecting magazines. Soon, checks poured in from across the country—which Eli, at 13, could not cash himself.

Despite the early entrepreneurial success, Eli spent the next decade of life working often difficult jobs to pay his way through college at Michigan State University, where he studied accounting and economics.

During his final year of college, Eli also met the woman who would become his wife. Edye Lawson was in her Senior year of high school when Eli received her phone number from a friend who thought the pair would make a good match. Eli cold called her, and to his surprise, she accepted. Within just a few months, Eli proposed marriage and Edye said yes. Within a few years, the Broads were the parents of two boys, Jeffrey and Gary.

Overall, the Foundation has invested more than $600 million in improving public education. Since 1999, The Eli and Edythe Broad Foundation sought ways to support the best public schools. Over the next two decades, the Foundation devoted tens of millions of dollars to helping urban public school systems.

The Broads’ philanthropy in the arts began before their work in education and science, and was largely spurred by Edye’s love of art. After they moved to Los Angeles in 1963 and Eli was working long days, Edye took to browsing L.A.’s famous galleries, like Ferus and Nicholas Wilder. Eli quickly caught on to the excitement of Edye’s hobby when she bought a print by an artist he had heard of—Toulouse-Lautrec.

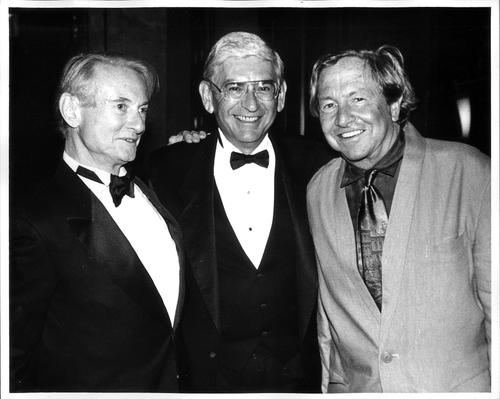

Eli began collecting under the guidance of famed MCA executive Taft Schrieber, who encouraged the Broads to buy their first major work, a Van Gogh ink drawing, at an auction in 1972. Within a few years of purchasing the Van Gogh, the Broads shifted their collecting to focus on contemporary art after they realized that the best art collections were built by acquiring the work of their time. Eli also discovered he enjoyed meeting the (still-living) artists. As he liked to say, “If I had to spend all my time with businessmen, lawyers and accountants, I’d be bored.”

Focusing on contemporary art also let Eli do what he most enjoyed—build institutions. In the late 1970s, Eli joined forces with fellow Los Angeles collector Marcia Weisman to help create a contemporary art museum for Los Angeles. Eli believed that the city that had given him so much—a chance to grow two businesses without the benefit of the right connections—deserved a great contemporary art museum. Weisman, along with Eli and several others, eventually convinced Los Angeles Mayor Tom Bradley to aggregate developer fees—commercial builders were required by city law to give 1.5 percent of their budgets to public art—to build a museum. Eli led a fundraising campaign that soon raised $13 million—including $1 million from him and Edye—for the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (MOCA).

Eli also helped secure the cornerstone of MOCA’s art collection using his skill for negotiation. Count Guiseppe Biumo di Panza, a board member of MOCA, had to sell 80 works from his vast collection of contemporary art due to a change in Italian tax law. Sotheby’s and Christie’s estimated that the trove—including seven Rothkos, 12 Klines, 11 Rauschenbergs, four Lichtensteins, eight Rosenquists, and 16 Segal sculptures, among others—would raise between $11 million and $15 million at auction. But Panza hated the idea of selling at an auction because the art would be sold piecemeal; he wanted the works to stay together as a collection.

Eli knew it was the perfect opportunity for MOCA, but his fellow trustees balked at the idea of dipping into their relatively tight budget for the collection. Broad persuaded them by emphasizing that it was an incredibly rare opportunity for a museum to buy in bulk and collect in depth with one purchase. He also hinted that, if the museum didn’t pony up, plenty of other private collectors might, including Eli himself. The trustees authorized him to make the purchase for no more than $12 million.

Within 24 hours, Eli negotiated the deal with Panza, managing to come in at $11 million for the collection with $2 million down, instead of the higher amount Panza wanted up front. Eli convinced Panza that a lower down payment would yield more money for him in the end because of the inflation of Italian currency. Today, the collection is worth more than $1 billion.

MOCA was the first of several efforts by Eli to support the revitalization of downtown Los Angeles, which had gone from a once vibrant commercial center in the early 1900s to a relatively under-developed region by the end of the 20th century. When Eli and Edye moved to the city in 1963, both were surprised by Los Angeles’ lack of a true civic center, in dramatic contrast to other major cities around the globe. Eli believed early on that his adopted home city required such a center if it were to be a major world metropolis. He seized every opportunity to help make that happen over the next several decades.

Within a few years of MOCA’s opening, Lillian Disney, the widow of famed animator Walt, donated $25 million to build a concert hall a block north of MOCA on Grand Avenue. But by the middle of the 1990s, no hall had been built because the city had been unable to raise the additional funds needed to execute architect Frank Gehry’s dramatic vision for the hall.

After more than two years of negotiating, Eli convinced the city and county governments to form a new entity—the Joint Powers Authority—to develop Grand Avenue into a walkable, livable, vibrant stretch of cultural and commercial destinations and residences.

Ultimately, what thwarted the Grand Avenue Project for several years was the 2008 financial crisis. (During the same crisis, The Broad Foundation saved MOCA from financial collapse with a $30 million grant.) Before funds dried up in the recession, however, Eli managed to secure a nonrefundable down payment from the developer, Related Companies. The $50 million plus interest went to creating Grand Park, connecting the Music Center with City Hall and becoming one of the rare green spaces in downtown Los Angeles. Grand Avenue is home to major architectural landmarks—including Arata Isozaki’s MOCA, the cathedral by Jose Rafael Moneo, an arts high school by Wolf Prix, and of course Gehry’s Disney Hall—and the mile-long stretch received millions of visitors a year (prior to the Covid-19 pandemic).

Building The Broad

While Grand Avenue redevelopment stalled, Eli was busy planning what he hoped would be an especially long-lasting legacy—a contemporary art museum devoted to showing the more than 2,000 artworks he and Edye had collected since their Van Gogh purchase in 1972.

Considered among the most prominent and important holdings of postwar and contemporary art in the world, the collections include in-depth representations from artists including Jeff Koons, Cindy Sherman, Roy Lichtenstein, Joseph Beuys, and dozens of others. Eli and Edye had collected while also supporting museums for decades—they gave $60 million to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art for the Renzo Piano-designed Broad Contemporary Art Museum, $33 million for the Broad Art Museum at MSU by Zaha Hadid and $23 million to UCLA for the Broad Art Center by Richard Meier, along with sizeable donations to New York’s Museum of Modern Art. The Broads had also supported their home city in a variety of other ways—helping to bring the Democratic National Convention to town in 2000, striving (unsuccessfully) to attract an NFL team to the city, and making attempts to buy the Dodgers and the Los Angeles Times (twice) when both were in difficult ownership situations.

In 2010, with Grand Avenue’s development stalled due to the recession, Eli and Edye decided to build their own museum on Grand Avenue, across the street from Disney Hall and MOCA. Holding an architectural competition for the museum, Eli emphasized that the museum would have to pursue a delicate balancing act—refrain from clashing with Disney Hall across the street while refusing to be an anonymous building.

The winning architects, Diller Scofidio + Renfro, proposed an idea that captured Eli and Edye’s vision of a public museum built around a private collection. Diller Scofiido + Renfro's “vault and veil” design included a dark, sculptural “vault” in the center of the museum to hold the Broads’ collection, while the museum itself was wrapped in a honeycomb “veil” allowing glimpses of the museum from Grand Avenue.

The museum, called simply The Broad, opened to international attention and acclaim on September 20, 2015, offering free general admission. For the Broads, the museum was the ultimate gift to their home city. “The city’s been good to me,” Broad always said. “And I want to give back.”

In one of his final public acts, Eli wrote an op-ed published in The New York Times, writing:

“Two decades ago I turned full-time to philanthropy and threw myself into supporting public education, scientific and medical research, and visual and performing arts, believing it was my responsibility to give back some of what had so generously been given to me. But I’ve come to realize that no amount of philanthropic commitment will compensate for the deep inequities preventing most Americans — the factory workers and farmers, entrepreneurs and electricians, teachers, nurses and small-business owners — from the basic prosperity we call the American dream…Our country must do something bigger and more radical, starting with the most unfair area of federal policy: our tax code…

The enormous challenges we face as a nation — the climate crisis, the shrinking middle class, skyrocketing housing and health care costs, and many more — are a stark call to action. The old ways aren’t working, and we can’t waste any more time tinkering around the edges."

_-3100x100_c.jpg)